Abstract

Excerpted from: "The Paradox of “Progressive Prosecution”, 132 Harvard Law Review 748 (December 2018) (153 Footnotes) (Full Document) (Student Note)

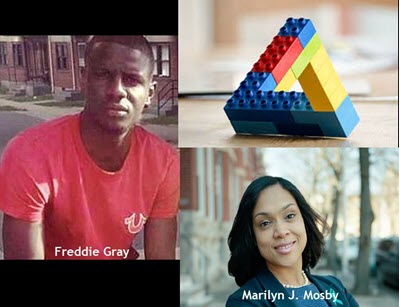

When Freddie Gray woke up on April 12, 2015, he surely did not know that he would soon enter a coma only to die a week later. That morning, he walked to breakfast in his old West Baltimore neighborhood with two of his best friends. The restaurant they wanted to visit was closed, however, so they left. At some point on the way home, they encountered police officers on bicycles. After a brief chase, Gray stopped voluntarily, at which point officers arrested him. Video footage shows the officers savagely shoving Gray's face into the sidewalk and twisting his arms and legs. Unable to stand or walk, Gray was dragged to the back of a police van where he would spend the next forty minutes handcuffed, shackled, unbuckled, and, while conscious, begging for his twenty-five-year-old life as the officers drove around the city making several stops. Eventually, Gray emerged unconscious with a nearly severed spinal cord and a crushed voice box. Paramedics later transferred him to the Maryland Shock Trauma Center, where he remained comatose for a week before dying.

When Freddie Gray woke up on April 12, 2015, he surely did not know that he would soon enter a coma only to die a week later. That morning, he walked to breakfast in his old West Baltimore neighborhood with two of his best friends. The restaurant they wanted to visit was closed, however, so they left. At some point on the way home, they encountered police officers on bicycles. After a brief chase, Gray stopped voluntarily, at which point officers arrested him. Video footage shows the officers savagely shoving Gray's face into the sidewalk and twisting his arms and legs. Unable to stand or walk, Gray was dragged to the back of a police van where he would spend the next forty minutes handcuffed, shackled, unbuckled, and, while conscious, begging for his twenty-five-year-old life as the officers drove around the city making several stops. Eventually, Gray emerged unconscious with a nearly severed spinal cord and a crushed voice box. Paramedics later transferred him to the Maryland Shock Trauma Center, where he remained comatose for a week before dying.

For five consecutive days, protesters took to the streets, City Hall, and the police headquarters to denounce Gray's death at the hands of the Baltimore police officers. Citizens and community leaders demanded that the city fire the officers and press criminal charges against them. After over a week of intensifying protests and national attention, State's Attorney Marilyn J. Mosby filed criminal charges against the six police officers who were involved in Gray's arrest and transportation to the police station.

The civil rights community celebrated this development, which came on the heels of officers in other jurisdictions being cleared of any wrongdoing for killing black men. Mosby was lauded for wielding her position as the city's chief prosecutor to insist on police accountability. Mosby herself seemed to have anticipated this support. At the press conference announcing the charges, she spoke directly to the protestors when she assured: "I heard your calls for ‘no justice, no peace!"' But things did not go according to plan. In a rousing press conference after the first three of the officers were acquitted, Mosby announced that she was professionally compelled to drop the charges against the remaining three officers despite the horrific injustice. She decried the trouble and pain "mothers and fathers all across this country, specifically Freddie Gray's mother Gloria Darden, or Richard Shipley, Freddie Gray's stepfather, [go] through on a daily basis knowing their son's mere decision to run from the police proved to be a lethal one." Despite the acquittals, she described Gray as an "innocent 25-year-old man who was unreasonably taken into custody after fleeing in his neighborhood, which just happens to be a high crime neighborhood."

Mosby's statements seem to imply that there was something inherently unfair about targeting Gray simply because he was in a high-crime area. It is deeply ironic for Mosby to make this argument. Just a few weeks before Gray's death, Mosby instructed the Division Chief of her office's Crime Strategies Unit to target the exact intersection where the officers first encountered Gray-- North Ave. and Mount St.--with enhanced drug enforcement efforts. Acting on this directive, the District Commander instructed the department lieutenants to conduct a daily narcotics initiative at that intersection, using cameras, informants, covert operations, and similar techniques. The initiative was an immediate priority and was expected to produce "daily measurables."

Mosby's unapologetic prosecution of the officers in Gray's case places her in the recently emerging league of "progressive prosecutors." But her zeal obscures her complicity. This Note interrupts the celebration of unusually progressive prosecutors to emphasize the risks associated with relying on prosecutors in the movement to reform the U.S. criminal legal system. It argues that these reforms are "reformist reforms" that fail to deliver on the transformative demands of a fundamentally rotten system.

Part I gives an overview of progressive prosecution tactics.

These tactics are deployed in a criminal legal system that is fundamentally rotten, as explained in Part II.

Part III outlines the inability of the progressive prosecution movement to redistribute power through ushering in transformative reforms.

Part IV provides guiding principles for future efforts in reform.

. . .

The paradox of "progressive prosecution" is that the criminal legal system is an oppressive institution. Attempting to make the "most powerful" actor in such an institution more progressive seems to miss the point. There is no doubt that people in Brooklyn and Philadelphia have enjoyed meaningful benefits from the District Attorneys' refusal to charge low-level marijuana offenders. But it is troubling that these benefits are so fortuitous--they are a product of how a prosecutor exercises her power. At the risk of seeming ungrateful, this Note argues we can and should do better. Doing better means confronting a regime controlled by dictators: not by asking them to be nice, but by demanding an entirely different form of government.