Become a Patreon!

Abstract

Excerpted From: Fern L. Kletter, COVID-19 Related Litigation: Effect of Pandemic on Release from Federal Custody, 54 American Law Reports Fed. 3d Art. 1 (2020) (39 Footnotes/extensive case citations) (Full Document Check Law Library)

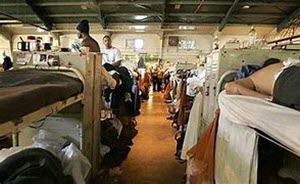

As the novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2 has spread throughout the United States, touching off widespread infections of the disease labeled COVID-19, a new challenge has arisen with respect to defendants in federal custody. Citing the threat of COVID-19 infection, many detainees have been petitioning for release from custodial detention. As spread of the virus is more likely when people are in close contact with one another within about six feet, detainees in correctional and detention facilities are at greater risk for COVID-19 due to the close living arrangements with others. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (also referred to in this article as "CDC") has specified steps for detention facilities to prepare for the possible spread of COVID-19, managing confirmed cases of the coronavirus and lowering the risk of staff and inmates getting the virus. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (also referred to in this article as "BOP") has also provided an emergency response and deployment of collaborative efforts to curb the spread of the virus. Still, there are concerns about the spread of COVID-19, as prisons generally are not conducive to social distancing and the infirmaries typically do not have the resources available to most hospitals. These concerns have prompted many federal inmates and detainees to file petitions for release from custody.

As the novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2 has spread throughout the United States, touching off widespread infections of the disease labeled COVID-19, a new challenge has arisen with respect to defendants in federal custody. Citing the threat of COVID-19 infection, many detainees have been petitioning for release from custodial detention. As spread of the virus is more likely when people are in close contact with one another within about six feet, detainees in correctional and detention facilities are at greater risk for COVID-19 due to the close living arrangements with others. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (also referred to in this article as "CDC") has specified steps for detention facilities to prepare for the possible spread of COVID-19, managing confirmed cases of the coronavirus and lowering the risk of staff and inmates getting the virus. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (also referred to in this article as "BOP") has also provided an emergency response and deployment of collaborative efforts to curb the spread of the virus. Still, there are concerns about the spread of COVID-19, as prisons generally are not conducive to social distancing and the infirmaries typically do not have the resources available to most hospitals. These concerns have prompted many federal inmates and detainees to file petitions for release from custody.

The Federal Bail Reform Act, 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142, governs the availability of bail in federal cases generally. Under the Act, the court is required to order the pretrial release of the accused, with conditions, unless such release will not reasonably assure the accused's appearance or will endanger the safety of another or the community. For certain specified offenses for which the accused was convicted while on release, however, there is a rebuttable presumption that no conditions will reasonably assure the safety of another and the community. Upon motion by the government in certain specified cases, and in a case that involves a serious risk of flight or a serious risk that the accused will obstruct justice or intimidate a witness or juror, the court is required to hold a hearing to determine whether any conditions will reasonably assure the accused's appearance and the safety of the community. In determining whether release is appropriate, the court considers the factors specified in 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(g): the nature and circumstances of the offense, the weight of the evidence against the accused; the history and characteristics of the accused; and whether the accused is a danger to another or the community.

Pretrial detainees have sought release due to the dangers of the COVID-19 pandemic, through a motion to reopen the detention hearing under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(f)(2), review of the original detention order, 18 U.S.C.A. § 3145(c), and temporary release under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(i). A detention hearing may be reopened under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(f)(2) if the court finds that new information exists material to the questions of flight and danger to the community. Pursuant to 18 U.S.C.A. § 3145(b), where an accused was ordered detained by a judicial officer other than the court having original jurisdiction over the offense, the accused may file with the court having original jurisdiction over the offense a motion for review of the detention order. Unlike a motion under § 3142(f)(2), § 3145(b) does not require a showing of a change of circumstances material to the questions of flight and danger to the community. The court may also permit temporary release under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(i) to the extent that it determines this to be necessary for preparation of the person's defense or for "another compelling reason."

Based on the particular circumstances of the case, courts have denied petitions for release brought under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(f)(2), alleging that the COVID-19 pandemic constituted new information material to the questions of risk of flight and danger, in which the detainee was awaiting trial on federal charges of violations of the Controlled Substances Act ( 4), firearms violations, human trafficking, sex trafficking, child pornography, kidnapping, carjacking, racketeering crimes, tax fraud, health care fraud, and other crimes of fraud and deception. In other cases, the COVID-19 pandemic was held, based on the specific facts, to constitute a change of circumstances that was material to the question of flight or danger and warranted release in cases in which the detainee was awaiting trial for violations of the Controlled Substances Act and firearms violations. Reviewing the circumstances of the particular case, courts have denied motions for reconsideration of a detention order based on the COVID-19 pandemic in cases in which the detainee was awaiting trial on federal charges of violations of the Controlled Substances Act and firearms violations. Based on the specific facts of the case, courts have denied temporary release under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(i), finding that the COVID-19 pandemic did not provide a compelling reason for release pending trial on violations of the Controlled Substances Act, firearms violations, continuing criminal enterprise, assault crimes, sex trafficking, child pornography, kidnapping, carjacking, bank robbery, Hobbs Act violations, racketeering crimes, money laundering, tax fraud, bank fraud, health care fraud, other crimes of fraud and deception, and in cases where the charges were not stated. In other circumstances, temporary release under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(i) was granted in cases pending trial on federal charges of violations of the Controlled Substances Act, firearms violations, sex trafficking, bank fraud, and in cases in which the charges were unstated.

Allegations have also been made that restrictions imposed by prisons due to efforts to contain the COVID-19 pandemic have impeded the detainee's ability to prepare a defense. Depending on the particular facts of the case, it was held that the COVID-19 pandemic did not constitute or did constitute a material change of circumstances pertaining to flight or danger under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(f)(2) to warrant relief on these grounds. Authority has also denied reconsideration of a detention/release order based on the accused's need to prepare a defense for an imminent trial. In other cases, it was held that the need to consult with counsel or to prepare a defense did not constitute or did constitute a compelling necessity for temporary release under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(i).

Authority has also considered claims of pretrial detainees that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, detention violated the Due Process Clause of U.S. Const. Amend. V, the right to counsel under U.S. Const. Amend. VI, and the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause of U.S. Const. Amend. VIII.

As a general rule, the court must order that a defendant convicted of an offense and awaiting the imposition or execution of sentence be detained, unless the court finds by clear and convincing evidence that the defendant is not likely to flee or pose a danger to another or the community if released. This, however, does not apply to a defendant convicted of a crime of violence, sex trafficking of children, certain terrorism offenses, and certain violations of controlled substances and drug enforcement laws. In such cases, the defendant must be detained, unless the court finds that there is a substantial likelihood that a motion for acquittal or a new trial will be granted or an attorney for the government has recommended that no sentence of imprisonment be imposed, and the defendant is not likely to flee or pose a danger to any other person or the community. In those cases in which the defendant cannot fulfill the requirements of 18 U.S.C.A. § 3143(a)(2)(A)(i) or 18 U.S.C.A. § 3143(a)(2)(A)(ii), 18 U.S.C.A. § 3145(c) creates a narrow exception, providing that a defendant who is neither a flight risk nor a danger to the community may be ordered released, under appropriate conditions, if it is clearly shown that there are exceptional reasons why detention would not be appropriate. As determined by the specific facts of the case, courts have denied requests for release pending sentencing, based on the COVID-19 pandemic, in cases mandating detention under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3143(a)(2), where the defendant was awaiting sentencing on federal charges of violations of the Controlled Substances Act, firearms violations, homicide, sex trafficking, child pornography, racketeering crimes, Hobbs Act violations, and bank robbery. Release due to the pandemic has also been denied in cases in which there was a presumption of detention under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3143(a)(1), pending sentencing on federal charges of violations of the Controlled Substances Act, firearms violations, racketeering crimes, securities fraud, and bank fraud. Under other particular circumstances, the courts have concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic warranted release in cases effectively mandating detention under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3143(a)(2), pending sentencing for federal charges of violating the Controlled Substances Act, firearms violations, child pornography, and racketeering. Release due to the pandemic was also granted in cases in which there was a presumption of detention under § 3143(a)(1), pending sentencing on federal firearms violations and crimes of fraud and deception. Claims for presentence release based on the coronavirus pandemic have also been made for temporary release under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(I); to reopen the detention hearing under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3142(f); and under U.S. Const. Amend. V and U.S. Const. Amend. VIII.

There is no federal constitutional right to be free pending an appeal, and the Bail Reform Act made it much more difficult for a convicted criminal defendant to obtain release pending appeal, since the Act's intent was that fewer convicted persons remain at large while pursuing their appeals. Generally, detention following conviction and sentencing is mandatory unless the court finds by clear and convincing evidence that if released, the person is not a flight risk or danger to the community, and the appeal is not for the purpose of delay and raises a question of law or fact likely to result in reversal, a new trial, a nonprison sentence, or a reduced sentence. Where, however, the defendant was convicted of a crime of violence, an offense with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment or death, or a controlled substances offense with a maximum sentence of 10 years or more, the defendant is subject to mandatory detention and may not be released pending appeal, unless exceptional reasons are shown why detention would not be appropriate and the defendant is not likely to flee or pose a danger. Requests for release pending appeal based on the COVID-19 pandemic were, in light of the particular facts of the case, denied in cases falling within 18 U.S.C.A. § 3143(b)(2), based on convictions for violations of the Controlled Substances Act, child pornography, racketeering crimes, and Hobbs Act violations, and in cases falling under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3143(b)(1) based on convictions for bank fraud and false use of passports or visas. Under the particular circumstances, release pending appeal was granted due to the pandemic in a case in which the specific charges were not stated. Also considered by authority was a petition for release pending appeal, due to the coronavirus pandemic, where only a petition for a rehearing en banc was remaining, and where the appeal was from the denial of a habeas corpus petition.

A federal court can reduce a prisoner's sentence under 18 U.S.C.A. § 3582(c)(1)(A), the "compassionate release" statute of the First Step Act, Pub. L. No. 115-391, if the court finds that extraordinary and compelling reasons warrant such a reduction, or, for certain offenders, if the prisoner is at least 70 years of age, the prisoner has served at least 30 years of the sentence, and a determination has been made by the BOP that the prisoner is not a danger to the safety of any other person or the community. In addition, the court is to consider, to the extent applicable, the factors set forth in 18 U.S.C.A. § 3553(a), including: the nature and circumstances of the offense and the history and characteristics of the defendant; the need for the sentence imposed to reflect the seriousness of the offense, promote respect for the law, provide just punishment, act as a deterrence, protect the public, and provide the defendant with needed educational or vocational training, medical care, or other correctional treatment; and any pertinent policy statement. According to the Application Notes in the Commentary to the current United States Sentencing Guidelines, which have not been updated since the passage of the First Step Act, extraordinary and compelling reasons for a sentence reduction include: the prisoner is suffering from a terminal illness; the prisoner is suffering from a serious physical or medical condition, a serious functional or cognitive impairment, or experiencing deteriorating physical or mental health because of the aging process that substantially diminishes the ability of the prisoner to provide self-care while incarcerated and recovery from the condition is not expected; or the prisoner is at least 65 years old and is experiencing serious deterioration in physical or mental health and has served at least 10 years or 75% of the term of imprisonment imposed; or the BOP has determined that there is an extraordinary and compelling reason for release other than or in combination with the reasons described.

[. . .]

Reviewing the particular facts before it, courts have denied compassionate release due to the COVID-19 pandemic in cases in which the defendant was serving a federal sentence for violations of the Controlled Substances Act, firearms violations, terrorism crimes, homicide, human trafficking, sex trafficking, child pornography, other federal sex crimes, kidnapping, carjacking, bank robbery, Hobbs Act violations, racketeering crimes, bribery, securities fraud, tax fraud, bank fraud, health care fraud, other crimes of fraud and deception, embezzlement and theft, and where the charges were unstated. In other circumstances, compassionate release based on the COVID-19 pandemic was granted in cases in which the defendant was serving a federal sentence for violations of the Controlled Substances Act, firearms violations, sex trafficking, child pornography, kidnapping, bank robbery, Hobbs Act violations, racketeering crimes, securities fraud, tax fraud, bank fraud, health care fraud, other crimes of fraud and deception, trade secrets crimes, a federal offense linked with a state offense, and offenses where the particular charges were not stated.

A petition for compassionate release can be filed by the BOP itself. In the alternative, a prisoner can file the petition if the prisoner has fully exhausted all administrative rights to appeal the BOP's refusal to bring a motion on the prisoner's behalf or 30 days have elapsed from the receipt of such a request by the warden, whichever is earlier. The courts are split, even within their particular district, on whether this exhaustion requirement may be waived in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Courts have held that the exhaustion requirement is not subject to a judicially crafted equitable exception, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, holding that strict compliance with the exhaustion obligations is required, whereas other courts have held that the compassionate release statute is subject to judicially created equitable exceptions, empowering the courts with the discretion to waive the exhaustion requirement, in the highly unusual circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some courts which hold that the exhaustion requirement is not judicially waivable have held that it is subject to government waiver or estoppel. Depending on the particular facts, courts have held in the particular case before it that the exhaustion requirement was not and was waived, and in other cases that the government was equitably estopped from asserting the requirement. In other cases, it was determined from the specific facts that the administrative remedies were exhausted.

Further pertaining to postsentence release requests due to the COVID-19 pandemic, authority has considered a request for temporary release under the compassionate release statute, a request for furlough and home confinement, the jurisdiction of the district court to hear a compassionate release motion or render an indicative ruling where the defendant's appeal is pending, and the authority of the court of appeals to decide a compassionate release motion.

Pertaining to proceedings for violation of a term of federal supervised release, as determined by the particular facts of the case, authority has denied a request for release on bail and for temporary release pending the violation hearing, and has denied and granted a request for release following imposition of sentence for a violation. Release has been denied and granted, depending on the circumstances, to a detainee pending extradition proceedings, due to the pandemic.

It has been held that a district court had no jurisdiction and had jurisdiction over a "conditions of confinement" claim of prisoners seeking habeas corpus relief based on the pandemic. Authority has also ruled that "deliberate indifference" was not established in a claim by detainees seeking injunctive relief due to the pandemic and that the Prison Litigation Reform Act barred a claim for injunctive relief brought by detainees seeking release due to COVID-19.

Become a Patreon!