Abstract

Lewis Bass and Thomas Parker Redick, U.S. Case Law Potentially Supporting Claims for Toxicogenomic Injury, Products Liability: Design and Manufacturing Defects § 29:3 (2d ed.) (November 2019 Update)

ProfRandall's Note: While this article is about product liability - it supports the claim for Descendants of African Enslaved in the United States (DAEUS) for health injuries caused by Slavery and Jim Crow. However, only a case maintained for DAEUS born and raised in Jim Crow has a chance of overcoming the statute of limitations.

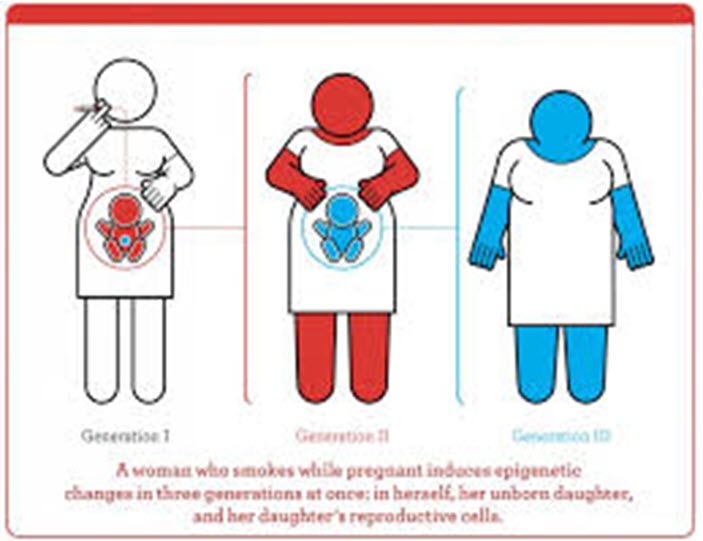

Toxicogenomic or epigenetic changes induced by toxins join psychological, nutritional and other environmental pressures that can alter genes and epigenetics to the detriment of living organisms. Defending claims based on toxicogenomics or epigenetics may require evidence delving into other factors that could have caused the genetic or epigenetic changes. Linkages to endocrine effects could occur at low doses, causing disruption leading to illness, cancer and other health problems. Current exposures could affect the health of not only individuals currently living but also future generations.

A genetically susceptible subclass seeking to use toxicogenomic evidence will be held to the same standards of causation. They have to demonstrate a relative risk of 2.0, known as "doubling of the risk," i.e., that the group exposed to a toxin has twice as many injured individuals with disease as the unexposed group. Therefore, courts have determined that a relative risk over 2.0 supports the assertion that a "plaintiff's disease was more likely than not caused by the implicated agent." Accordingly, a number of courts require a relative risk of 2.0 or greater for a plaintiff to satisfy the burden of proof on general causation. Courts that allow epidemiological data to satisfy specific causation—the "weak" view—may also require plaintiffs to meet a relative risk cutoff of 2.0; Texas requires a relative risk of 2.0 or greater before allowing epidemiological data to satisfy general causation. The Third Restatement of Torts follows this model, requiring a relative risk of over 2.0 before an epidemiological study may be submitted to the jury for specific causation. Other courts find that in groups of plaintiffs who have the same occurrence of disease as the non-exposed background population, then the risks are identical and the relative risk is 1.0, which does not demonstrate a higher incidence of disease.

For plaintiffs, genetic and epigenetic evidence provides a new approach to showing the biological plausibility of their medical causation claim. In cases where the onset of cancer or other disease occurs later in life, decades after exposure (or intergenerationally), the claim may suffer from latency and run afoul of statutes of limitation or repose.

The passage of time may also lead to difficulty in tracing back to link the product and seller to the plaintiff's harm ("product identification"). In the context of environmental and toxic harms, one of the primary roles the tort system is considered to fill is a regulatory public health role. In other words, the tort system sends deterrent signals to environmental harm producers via those who are injured and legally pursue claims against these producers. However, "[e]mpirical evidence suggests that environmental tort suits" send "a weak deterrent signal." In theory, a person harmed by toxic waste seeping from an industrial factory can bring a tort claim, receive compensation for his or her injuries, and deter future exposures. In practice, studies have shown that such individuals are unlikely to receive tort compensation. A typical toxic waste disposal injury is intrinsically different from the particularized, immediate harms around which tort law developed. The lapsed time between the disposal and injury and the inherently diffuse nature of causation generally act to discourage these claims. In addition, potential plaintiffs for these claims face stiff practical barriers to accessing the judicial system, such as high financial costs.

If new genetic or epigenetic data suggests harm to "eggshell genes" (i.e., genetic susceptibilities), plaintiffs' attorneys in the U.S. may increasingly file mass tort "fear of cancer" lawsuits against chemical companies, alleging that genetically susceptible potential subclasses have unique biomarkers or have increased risk due to genes that make them more likely to develop illness from exposure, even at a dose below regulatory guidance on exposures. In some cases, companies may decide to forego marketing products that may actually be very beneficial to the vast majority of users. Such decisions may occur in advance of any regulatory decision to recall the product.

The seminal case on medical monitoring for fear of cancer based upon genetic damage from a hazardous chemical is Ayers v. Jackson Township. In Ayers, over 300 plaintiffs alleging exposure to toxic substances in drinking water (leading to a "genetic switch" ready to turn cancerous in the future) were allowed to recover medical monitoring costs based on a largely unquantified excess risk substantiated by expert opinion about a reasonable likelihood of future illness.

As befits the state that considers itself the US leader in environmental protection, California took medical monitoring and lowered the level of causation required to prove a reasonable fear of cancer, in cases where malicious concealment of toxic exposure has occurred. In 1984, the owners of property near a California landfill discovered toxic chemicals in their home water wells and sued the corporate owners of a neighboring Firestone plant, seeking medical monitoring and damages for emotional distress, based upon their fear of future cancer.

The California Supreme Court, in Potter v. Firestone, set forth guidelines for fear of cancer claims:

[I]n the absence of a present physical injury or illness, damages for fear of cancer may be recovered only if the plaintiff pleads and proves that

(1) as a result of the defendant's negligent breach of a duty owed to the plaintiff, the plaintiff is exposed to a toxic substance which threatens cancer; and

(2) the plaintiff's fear stems from knowledge, corroborated by reliable medical or scientific opinion, that it is more likely than not that the plaintiff will develop cancer in the future due to toxic exposure. (emphasis added)

According to most experts, proving a probability of cancer from genetic or epigenetic harm is going to be very difficult.

As an exception to this general rule of proof, however, plaintiffs who have no physical injury or illness can have a lower standard of proof for damages for negligently inflicted emotional distress if the plaintiff pleads and proves that:

(1) as a result of the defendant's negligent breach of a duty owed to the plaintiff, he or she is exposed to a toxic substance which threatens cancer;

(2) the defendant, in breaching its duty to the plaintiff, acted with oppression, fraud or malice as defined in Civil Code section 3294; and

(3) the plaintiff's fear of cancer stems from knowledge, corroborated by reliable medical or scientific opinion, that the toxic exposure caused by the defendant's breach of duty has significantly increased the plaintiff's risk of cancer and has resulted in an actual risk of cancer that is significant.

The court further stated that medical monitoring "costs are a compensable item of damages in a negligence action where the proofs demonstrate, through reliable medical expert testimony, that the need for future monitoring is a reasonably certain consequence of the plaintiff's toxic exposure and that the recommended monitoring is reasonable."

With the level of "significance" is set as low as a mere doubling of background risk of cancer, the use of toxicogenomics evidence to establish a genetic susceptibility can readily establish "significant" risks to exposed individuals. Since the defense conduct allowing this lower standard of proof will also provide ground for punitive damages, defendants will need to ensure that they warn adequately—including genetically susceptible individuals if "knowable" risks exist. Otherwise, this double trap of lowered proof and punitive damages risk for "concealing" knowledge of risk could lead companies into a serious liability.

If adequate proof of product safety is maintained through testing and literature reviews relating to product risks, then a solid defense can be brought when plaintiffs use toxicogenomic effects (e.g., biomarkers in DNA) in an attempt to establish exposure to a particular substance. For example, DNA damage has been detected in benzene exposed workers. However, the findings of the DNA damage measures have not found widespread acceptance as biomarkers of exposure or effect with benzene mediated disease. The defense in these benzene cases may have succeeded in some instances, but cases are still being brought. A pending lawsuit alleges that Texaco and Chevron are responsible for the death of a former employee who was exposed to dangerous levels of benzene while on the job.

[. . .]

While the "idiosyncratic reaction" defense, discussed in § 4:7, supra, may still be used in some jurisdictions where toxicogenomic information is not considered "state of the art" and genetic susceptibilities are not reasonably foreseeable, manufacturers selling into California (which has a narrow defense of idiosyncratic reaction and low threshold for cancerphobia claims) will need to be cautious with regard to liability risks to the genetically susceptible.