Abstract

Excerpted From: Julian V. Roberts, Gabrielle Watson and Rhys Hester, Sentencing Members of Minority Groups: Problems and Prospects for Improvement in Four Countries, 52 Crime and Justice 343 (2023) (32 Footnotes/References) (Full Document Requested)

Racial, ethnic, and Indigenous minorities have long accounted for a disproportionate percentage of prison admissions in Western nations. The minorities affected vary, as does the magnitude of the problem. The explanations are complex and interrelated. The historical experiences of ethnic, racial, and Indigenous minorities play a role, particularly in postcolonial societies. Socioeconomic disadvantage and exposure to risk factors for offending such as unemployment, alcohol, and drug abuse are proximate causes of over-representation. Discriminatory treatment by criminal justice officials also contributes. Much media and professional attention focuses on sentencing, where the consequences for defendants are most significant and decision-making is most public. A large body of research identifies sentencing as a cause--or, at the very least, an amplifier--of minority over-incarceration.

Racial, ethnic, and Indigenous minorities have long accounted for a disproportionate percentage of prison admissions in Western nations. The minorities affected vary, as does the magnitude of the problem. The explanations are complex and interrelated. The historical experiences of ethnic, racial, and Indigenous minorities play a role, particularly in postcolonial societies. Socioeconomic disadvantage and exposure to risk factors for offending such as unemployment, alcohol, and drug abuse are proximate causes of over-representation. Discriminatory treatment by criminal justice officials also contributes. Much media and professional attention focuses on sentencing, where the consequences for defendants are most significant and decision-making is most public. A large body of research identifies sentencing as a cause--or, at the very least, an amplifier--of minority over-incarceration.

Sentencing can exacerbate racial, ethnic, and Indigenous differences arising at earlier stages of the process. Overt discrimination may result in minority offenders being more likely to receive prison sentences, and for longer terms. Indirect discrimination also contributes. Elements of sentencing law, sentencing guidelines, and professional practice can have differential effects on minority offenders. Examples include guilty plea sentence discounts, criminal history enhancements, and the application of aspects of mitigation such as remorse. The challenge to legislators and sentencing commissions has been to devise solutions that reduce or eliminate sentencing differentials without undermining fundamental sentencing principles such as equity and proportionality.

Terms we use in this essay--race, ethnicity, minority ethnic, and marginalized--are imperfect. There has been variability in how these categories are understood and applied in criminal justice scholarship. For example, it is unclear what groups are included within the British term “minority ethnic.” The term “marginalized” is too general, although it has historically been associated with punitive outcomes. New terms may allow for greater analytical granularity.

Two theoretical accounts--disparate treatment and differential impact-- offer valuable insights but do not capture the full picture. According to the disparate treatment perspective, racial and ethnic disparities result from discriminatory decisions by practitioners in individual cases. Minority defendants are often treated more harshly, even after accounting for legal factors such as prior convictions and offense seriousness. This perspective is too quick to align disparate treatment with bias. The differential impact perspective, by contrast, highlights laws and policies that, although applied neutrally to all racial and ethnic groups, are constructed in ways that make members of minority groups especially vulnerable to their effects (Murakawa and Beckett 2010). Taken together, the disparate treatment and differential impact accounts are of limited application to jurisdictions with Indigenous populations since they do not explain their overrepresentation at sentencing and disregard colonial and postcolonial legacies.

Accounting for the exact cause, or combination of causes, of over-representation is a complex task. The explanations vary, especially as these populations become larger and more heterogeneous. We caution against an overly reductionist account that seeks to explain minority overrepresentation only in terms of matters originating outside of the justice system, such as socioeconomic disadvantage or exposure to risk factors for offending. Sentencing is too context sensitive to be explained by a single theoretical account. The most plausible account of minority overrepresentation would be pluralist in nature, reflecting both direct (institutional) and proximate (socioeconomic) causes. There are tensions between the accounts on offer. They are not strictly distinct or irreconcilable, and it is neither necessary nor desirable to force a choice between them.

Although ethnic, racial, and Indigenous overincarceration is a common phenomenon, the solutions proposed or implemented at sentencing have been jurisdiction specific. We provide a cross-jurisdictional examination of developments in four countries and of the--at best modestly successful-- solutions that have been tried. We address three key questions. First, do sentencing outcomes differ for racial, ethnic, and Indigenous minority defendants? Second, to what extent are marginalized communities overrepresented in prison statistics? Third, what kinds of remedial steps have legislatures, sentencing commissions, and courts taken?

A number of conclusions emerge:

Minority defendants (particularly Indigenous and First Nations peoples) are overrepresented in the prison populations of all four countries. The persistence of high rates of minority imprisonment suggests that the primary drivers lie outside the jurisdiction of the sentencing court. The principal causes are found earlier in the criminal process and in the socioeconomic conditions to which marginalized and racialized minorities are subject.

Data deficiencies limit our ability to determine to what degree minority over-incarceration is attributable to sentencing. Imprisonment statistics are often uncorrected for offenders' criminal histories or other legally relevant factors. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that direct and indirect discrimination at sentencing contributes to racial and ethnic disproportionality.

Discretionary and structured sentencing regimes contain features that disadvantage minority defendants and create sentencing and imprisonment disparities. The differences vary considerably according to offense, minority background, and characteristics of the individual offender. Indigenous and Black communities fare worst.

Legislators and sentencing commissions have been slow to address the problem. Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand have enacted special provisions for the sentencing of Indigenous offenders, but this alone has proved insufficient.

Sentencing commissions carry a special responsibility to ensure that their guidelines do not exacerbate existing differences between majority and minority defendants. Most US commissions have abdicated their responsibility in this respect. US sentencing commissions and courts have generally adopted a “color-blind” approach to sentencing of members of minority group. Judges and other policy makers in the other three countries have attempted to address the problem.

The Sentencing Council of England and Wales alerts judges to sentencing differentials involving minorities but offers no guidance regarding the sentencing of these groups.

The Canadian Parliament has legislated particular consideration be given to sentencing Indigenous offenders. In addition, courts in Canada sentence Indigenous offenders with the benefit of specialized reports, often prepared by Indigenous legal officers. Similar consideration is now being extended to Black offenders with a history of racial abuse or discrimination.

Legislation in Aotearoa New Zealand has codified special consideration for Mori and other disadvantaged defendants. Courts now recognize that defendants from marginalized communities have legitimate claims to mitigation arising from racial abuse or discrimination that may have contributed to their offending or affected their level of culpability. Despite these (and other) remedial initiatives, racial, ethnic, and Indigenous overincarceration persists.

Correcting elements of sentencing law, policy, and practice that exacerbate racial disproportionality is possible, although it will require bold action from legislatures, governments, sentencing commissions, and courts. Judges are unlikely to adjust their sentences without appropriate guidance or authority from appellate courts or commissions. They, in turn, are unlikely to act without encouragement from the legislature.

This essay is organized as follows. Section I documents the disproportionality problem and responses to it in the United States, England and Wales, Canada, and Aotearoa New Zealand. The first two jurisdictions operate formal sentencing guidelines. The latter are representative of the discretionary approach found in most common law countries. The United States is the home of the sentencing guidelines movement; reduction in racial disparities at sentencing (and in prison populations) was one of the justifications for its introduction. The Sentencing Council of England and Wales has recently reviewed its guidelines to understand whether and how they contribute to racial differences in sentencing. Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand have sizable Indigenous populations and have grappled with minority overincarceration for decades. Legislatures and the courts have taken the initiative in these countries. Section II explores other potential remedies.

[. . .]

In this essay we have explored divergent responses in four countries to the overrepresentation of members of racial, ethnic, and Indigenous minorities among prisoners. Despite some modest remedial initiatives, differential sentencing practices persist in all four countries, as does over-representation. The authorities responsible for state punishment-- legislatures, commissions, and courts--cannot alone remedy racial, ethnic, and Indigenous overincarceration, but it is incumbent upon them to take bolder action. One conclusion seems clear: a “color-blind” approach denies minority offenders of appropriate consideration of race-related factors that may diminish their culpability. Minority defendants are doubly disadvantaged--by society in general and by the criminal justice system--when the relevance of race and ethnicity is ignored.

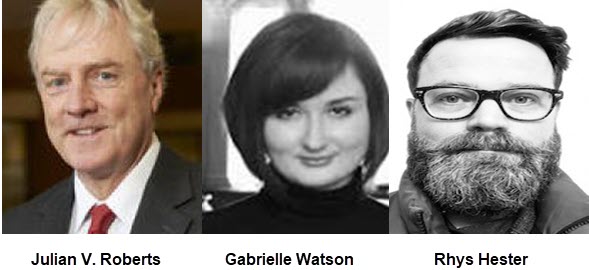

Julian V. Roberts is professor of criminology emeritus at the University of Oxford.

Gabrielle Watson is chancellor's fellow at Edinburgh Law School.

Rhys Hester is assistant