Abstract

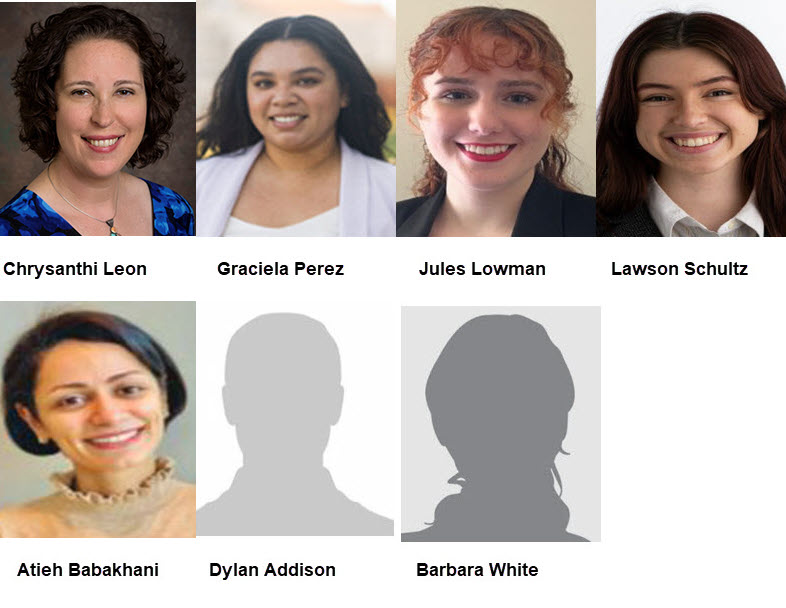

Excerpted From: Chrysanthi Leon, Graciela Perez, Jules Lowman, Lawson Schultz, Atieh Babakhani, Dylan Addison and Barbara White, “The More Connection the Better”: Bounded Relationships and Uneasy Alignments in Prison Education, 27 Journal of Health Care Law and Policy 152 (2024) (111 Footnotes) (Full Document)

The Journal's 2023 Symposium brought an interdisciplinary group together to explore and discuss the implications of legal coercion as therapeutic intervention, drawing attention to the consequences of such uneasy alignments. This Article will use a case study of one such program to explore the implications for systems with opposing approaches to human agency and well-being that is analogous to many of the uneasy alliances discussed at the Symposium and explored in this special Issue. The prison classroom serves as an example of a soft place within a hard place that provides “open-heartedness and care” within “the inherently harsh prison system.” A tradition among critical scholars and activists like Cheliotis calls us to consider whether we should continue working on incremental improvements in systems that we know to cause harm, or whether we should remove our energies and work on wholly different responses, including social movements that would secure a broader sense of well-being for all and build solidarity across communities. We take seriously the work of prison abolitionists “trying to attend to the immediate needs of those trapped in this system while working towards the long term aim of dismantling it.” Specific to prison programing, Cheliotis cautions against the trend in criminological scholarship to focus “disproportionately on the development and effectiveness of formalised practitioner-run prison programmes which claim to 'empower and rehabilitate”’ and may approach research evaluation “uncritically, devoid of the socio-political dimensions of their context, content, conduct and consequences.”

The Journal's 2023 Symposium brought an interdisciplinary group together to explore and discuss the implications of legal coercion as therapeutic intervention, drawing attention to the consequences of such uneasy alignments. This Article will use a case study of one such program to explore the implications for systems with opposing approaches to human agency and well-being that is analogous to many of the uneasy alliances discussed at the Symposium and explored in this special Issue. The prison classroom serves as an example of a soft place within a hard place that provides “open-heartedness and care” within “the inherently harsh prison system.” A tradition among critical scholars and activists like Cheliotis calls us to consider whether we should continue working on incremental improvements in systems that we know to cause harm, or whether we should remove our energies and work on wholly different responses, including social movements that would secure a broader sense of well-being for all and build solidarity across communities. We take seriously the work of prison abolitionists “trying to attend to the immediate needs of those trapped in this system while working towards the long term aim of dismantling it.” Specific to prison programing, Cheliotis cautions against the trend in criminological scholarship to focus “disproportionately on the development and effectiveness of formalised practitioner-run prison programmes which claim to 'empower and rehabilitate”’ and may approach research evaluation “uncritically, devoid of the socio-political dimensions of their context, content, conduct and consequences.”

Our contribution developed in this Article, the concept of “bounded relationships,” is informed by feminist research that attends to the wisdom and agency exhibited by people who may otherwise be thought of as “less than.” For example, Rosen and Venkatesh describe sex workers in a Chicago housing project who employ “bounded rationality,” a process by which they make decisions in order to solve a problem quickly and locally, whether or not the decision is “optimal or desirable in the abstract.” In what appears analogous, students in Inside-Out prison education courses engage in bounded relationships, relying on the trust and empathy they have built through the deliberate pedagogical practices promoted by Inside-Out, to benefit from the academic and personal growth that these courses make possible. They know the relationships are bounded by the semester and other restrictions, but they each make choices to connect, often through shared vulnerability.

While the focus in this Article will center on understanding the tensions between student-centered pedagogy and institutional goals of rehabilitation and punishment, the Article is situated in a broader area of critical scholarship that uses data from people most impacted by such programs to explore “the controversial marriage of rehabilitative and penal practices ... [and the] complex interplay between different forms of coercion and rehabilitation.

[. . .]

The interim approach we now employ is to keep the most directly impacted at the center as best we can. Too often, researchers, academics, and advocates attempt to provide a “voice for the voiceless,” and instead, reinforce that community's silence; research often lacks contextualized information, giving an audience “just enough information to do harm.” As we model in this analysis, rather than hide behind our qualms, we bring our perspectives and research tools and we remain engaged, we listen, and we keep working at the micro level, as well as the meso and macro levels. There are several directions which future research can profitably take. However, methodologically, our findings on the value of relationships and our attention to the pitfalls of confirmation bias together point to the importance of research that is led by those who are directly impacted. While difficult to organize, participatory action research and relational methodologies are necessary to overcome confirmation bias and address power differentials.

Chrysanthi Leon, Professor, University of Delaware, Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, Newark, DE, USA.

Graciela Perez, Assistant Professor, James Madison University, Department of Justice Studies, Harrisonburg, VA, USA.

Jules Lowman, JD student, Fordham University, School of Law, New York, NY, USA.

Lawson Schultz MURP Student, University of Michigan, Taubman College, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

, Atieh Babakhani, Assistant Professor, Ramapo College of New Jersey, School of Social Science and Human Services, Mahwah, NJ, USA.

Dylan Addison PhD. Independent Community-Engaged Researcher, Liberatory Insights Research Collective, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Barbara White,BSN, MSN, retired, Wilmington, DE, USA.