Abstract

Memorandum Opinion the Cherokee Nation V, Raymond Nash, et Al., Marilyn Vann, et Al., Ryan Zinke, Secretary of the Interior, and the United States Department of the Interior, United States District Court for the District of Columbia , Civil Action No. 13-01313 (2017)(FULL OPINION) (100+ pages)

Although it is a grievous axiom of American history that the Cherokee Nation’s narrative is steeped in sorrow as a result of United States governmental policies that marginalized Native American Indians and removed them from their lands, it is, perhaps, lesser known that both nations’ chronicles share the shameful taint of African slavery. This lawsuit harkens back a century-and-a-half ago to a treaty entered into between the United States and the Cherokee Nation in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Although it is a grievous axiom of American history that the Cherokee Nation’s narrative is steeped in sorrow as a result of United States governmental policies that marginalized Native American Indians and removed them from their lands, it is, perhaps, lesser known that both nations’ chronicles share the shameful taint of African slavery. This lawsuit harkens back a century-and-a-half ago to a treaty entered into between the United States and the Cherokee Nation in the aftermath of the Civil War.

In that treaty, the Cherokee Nation promised that “never here-after shall either slavery or involuntary servitude exist in their nation” and “all freedmen who have been liberated by voluntary act of their former owners or by law, as well as all free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months, and their descendants, shall have all the rights of native Cherokees . . . .” Treaty With The Cherokee, 1866, U.S.-Cherokee Nation of Indians, art. 9, July 19, 1866, 14 Stat. 799 [hereinafter 1866 Treaty].

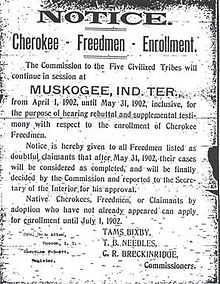

The parties to this lawsuit have called upon the Court to make a judicial determination resolving what they believe to be the “core” issue in this case, which is whether the 1866 Treaty guarantees a continuing right to Cherokee Nation citizenship for the extant descendants of freedmen listed on the Final Roll of Cherokee Freedmen compiled by the United States Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes, also known as the “Dawes Commission.”

Treaty guarantees that extant descendants of Cherokee freedmen shall have “all the rights of native Cherokees,” including the right to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation, the Court will deny the Cherokee Nation’s motion for partial summary judgment and grant both the Interior’s and Cherokee Freedmen’s motions. The Cherokee Nation’s motion to strike will be denied as moot.

. . .

The ultimate issues in this case are weighty and the competing interests and equities reflect the casualties of profound acts of injustice, indignity and demoralization committed during anguished times in our nation’s history. And while both the Cherokee Freedmen and the Cherokee Nation are victims of that history in different, albeit intertwined, respects, it cannot be gainsaid that the Cherokee Freedmen bear no culpability for the course of historical acts and agreements that ultimately ushered them to this Court and over which they commanded no voice, representation or power. The Court finds it confounding that the Cherokee Nation historically had no qualms about regarding freedmen as Cherokee “property” yet continues, even after 150 years, to balk when confronted with the legal imperative to treat them as Cherokee people. While the Cherokee Nation might persist in its design to perpetuate a moral injustice, this Court will not be complicit in the perpetuation of a legal injustice.

There appears to be no dispute that the Cherokee Freedmen are descendants of freedmen who were held as slaves by Cherokees and ultimately listed on the Dawes Freedmen Roll. Article 9 of the Treaty of 1866 entitles them to “all the rights of native Cherokees,” 14 Stat. at 801, which means they have a right to citizenship so long as native Cherokees have that right. Nothing in the 1866 Treaty qualified that right by subjecting it to a condition antecedent that would terminate it, including the extinction of Indian Territory upon Oklahoma statehood. Although the Cherokee Nation Constitution defines citizenship, Article 9 of the 1866 Treaty guarantees that the Cherokee Freedmen shall have the right to it for as long as native Cherokees have that right. The history, negotiations, and practical construction of the 1866 Treaty suggest no other result.

Consequently, the Cherokee Freedmen’s right to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation is directly proportional to native Cherokees’ right to citizenship, and the Five Tribes Act has no effect on that right. The Five Tribes Act did not abrogate, amend or otherwise alter Article 9’s promise that descendants of freedmen shall have all the rights of native Cherokees. The Cherokee Nation’s sovereign right to determine its membership is no less now, as a result of this decision, than it was after the Nation executed the 1866 Treaty. The Cherokee Nation concedes that its power to determine tribal membership can be limited by treaty. Cherokee Nation’s Mem. In Support of Mot. for Summ. J. 21, ECF No. 233.

The Cherokee Nation can continue to define itself as it sees fit but must do so equally and evenhandedly with respect to native Cherokees and the descendants of Cherokee freedmen. By interposition of Article. 9 of the 1866 Treaty, neither has rights either superior or, importantly, inferior to the other. Their fates under the Cherokee Nation Constitution rise and fall equally and in tandem. In accordance with Article 9 of the 1866 Treaty, the Cherokee Freedmen have a present right to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation that is coextensive with the rights of native Cherokees.

. . .

For all the foregoing reasons, the Court will deny the Cherokee Nation and Principal Chief Baker's Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, and grant the Cherokee Freedmen's Cross-Motion for Partial Summary Judgment as well as the Department of the Interior's Motion for Summary Judgment. Because it was unnecessary for the Court to either review or rely on the expert report that was submitted as Exhibit 3 to the Department of the Interior's Motion for Summary Judgment, the Cherokee Nation and Principal Chief Baker's Motion to Strike Expert Report of Emily Greenwald will be denied as moot.