Become a Patron!

Vernellia R. Randall, Taking a Community Approach to Preventing the Creation of a Biological Underclass, Chapter Four, Families and Communities in Partnership, edited by Patricia Voydanoff, 43-68 (University Press of America 1996)

Notes: This paper is limited to fetal alcohol syndrome because alcohol abuse provides a good paradigm for analyzing all substance abuse. Furthermore, the problem is not complicated by the illegality of its use. This paper is limited to a discussion of the impact of maternal drinking during pregnancy on the unborn child. This is not to minimize the potential impact that paternal alcohol abuse may have o the unborn child. Paternal drinking is known to reduce sperm counts and sperm motility and to produce other sperm abnormalities. However, this does not directly affect the unborn child. While paternal drinking may also contribute to fetal abnormalities, the limited studies that have been done have not found such an effect.

Each year, thousands of children are born severely damaged by maternal alcohol abuse) Fetal Alcohol Syndrome' is the leading known cause of mental retardation (ranking ahead of Down's syndrome and spina bifida).

Each year, thousands of children are born severely damaged by maternal alcohol abuse) Fetal Alcohol Syndrome' is the leading known cause of mental retardation (ranking ahead of Down's syndrome and spina bifida).

This problem is not new. Since the beginning of recorded history, women have consumed alcoholic beverages in religious ceremony, in celebration, for medicinal therapy, and in recreation. Historians have recognized and reported the impact of problem drinking on the fetus.' Hippocrates warned pregnant women not to take drugs before the fourth month and after the seventh month.' Soranus of Ephesus warned women not to take drugs especially during the first trimester:

Let no one assume that the fetus has not been injured at all. For it has been harmed: It is weakened, becomes retarded in growth, less well nourished, and in general, more easily injured and susceptible to harmful agents; it becomes misshapen and of ignoble sou1.

Without minimizing the general oppression of women, it is no surprise that society has generally disapproved of women drinking alcohol. In ancient Rome, women were strictly prohibited from drinking alcohol and were punished by stoning or starvation for breaking the prohibition." In Philistines, according to chapter 13 of the Book of Judges, an angel appeared to the wife of Manoah and told her: "Behold . . . you shall conceive and bear a son. Therefore beware, and drink no wine or strong drink, and eat nothing unclean." She followed the injunction and bore the hero Samson. Because of that biblical story, alcohol drinking by pregnant women has been taboo for many people.

Centuries later, Kant attributed the sobriety of women of his time to their special place." While Kant's observation may reflect the sexism that historically has oppressed women, his observations also support, indirectly, what social scientists have documented. Whenever the cultural bars to female drinking fall, the incidence of prenatal alcohol injury rises and the harm to communities and society escalates.' "Whatever the root of the ancient restrictions, they have for millennia had the effect of promoting healthy births."'

The lifting of the prohibition against women drinking in our society can, in part, be traced to the 1940's when the country repealed national prohibition, the depression was ending, and the country was reluctantly preparing for war.-There was little national interest in alcohol-related problems. Alcoholics were heavily stigmatized, assumed to be of little worth, and usually blamed for their condition. While the society was concerned about intoxication, there was a widespread reluctance to enforce anti-drunkenness controls'

Society dismissed as a myth the association between women's alcohol use and birth defects." This change in attitude toward the impact of women's drinking coupled with less patriarchal oppression resulted in a significant increase in drinking and alcohol problems in women.7 For instance, women born during the 1950's and 60's show a higher rate of heavy-frequent drinking than the generations of women before them.7 Furthermore, the risk of alcoholism in the present generation of women closely approximates that of men in their fathers' generation." Today, it is as acceptable for women to drink alcohol as men. In fact, 3.5 million American women use alcohol inappropriately and suffer from

One of the tragedies of the twentieth century is Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). As a result of FAS, three babies out of every thousand are born mentally, emotionally, and behaviorally retarded. The tragedy goes beyond the impact on the individual. FAS individuals form a self- generating, renewable, biological underclass (bio-underclass). Such an underclass has significant impact on the community and can potentially destroy it. Although FAS is completely preventable, efforts to prevent FAS break down over the debate about individual rights, that is, maternal rights and fetal rights. Individual rights' discussion in this context demonstrates the inadequacy of the rights language in an age of pluralism and diversity. FAS is a prime example of the need for a revised analytical structure. Such a revised structure would include the languages of interdependency, responsibility, and commitment to communities.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome as a Community Health Issue

FAS is a community health issue because it imposes a significant economic cost on the community, it is totally preventable and it creates a biological underclass.

Significant Economic Cost

Aside from the personal impacts, the social and economic costs are dramatic over the lifespan of the FAS victims. For example, in 1983 alcohol abuse and alcoholism cost our economy $117 billion a year. In comparison, nonalcoholic drug abuse that year cost $60 billion. Costs of alcohol abuse are projected to rise to $150 billion in 1995. Thus, the effects of alcohol abuse and alcoholism are as damaging to our nation's economy as they are to our nation's health.'

Preventable

At the present time the fetal alcohol syndrome rate is 1 to 3 per 1,000 live births. This statistic is particularly disturbing since it is the only form of mental retardation which is entirely preventable.'"-" That is, if a woman does not consume alcohol during pregnancy, then the unborn child will not be affected. Yet, those who place a high value on personal autonomy reject any infringement on voluntary personal assumption of health risks.' The absolute preservation of these rights comes at the risk of impairment or death to the individual and ultimately to the community. Thus, future community planning and decision making must develop a legally supportable approach to preventing fetal alcohol syndrome even though it is an impairment produced by personal life-style choices.'

Creates a Biological Underclass

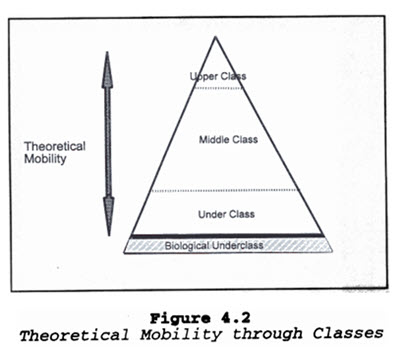

The most significant problem for society is that alcohol abuse during pregnancy creates a biological underclass. We have in America been reluctant to accept the existence of classism in our society. We have only been willing to so in the context that classism exists with theoretical mobility. (See Figure 4.1). The three-tiered conception of class (Upper, Middle and Lower) is the way class is usually thought of in this society.' It is within this structure of class that upward mobility has been the essence of the American dream."' In the new land of democracy and freedom, everyone who tried hard enough could rise and become rich. Individual initiative and persistence were automatic stair steps to financial success and upward mobility.

The most significant problem for society is that alcohol abuse during pregnancy creates a biological underclass. We have in America been reluctant to accept the existence of classism in our society. We have only been willing to so in the context that classism exists with theoretical mobility. (See Figure 4.1). The three-tiered conception of class (Upper, Middle and Lower) is the way class is usually thought of in this society.' It is within this structure of class that upward mobility has been the essence of the American dream."' In the new land of democracy and freedom, everyone who tried hard enough could rise and become rich. Individual initiative and persistence were automatic stair steps to financial success and upward mobility.

It is has been our dogged belief that given hard work any one can rise up the ladder. And while history has been filled with instances of sociocultural limitations (i.e., sex and race) to fulfilling the American dream, we have been equally diligent in removing all legal barriers to "equal opportunity." While we have recognized that some individuals, because of biology (i.e., mentally retarded), do not have the same access to mobility, we have viewed the problem as isolated.

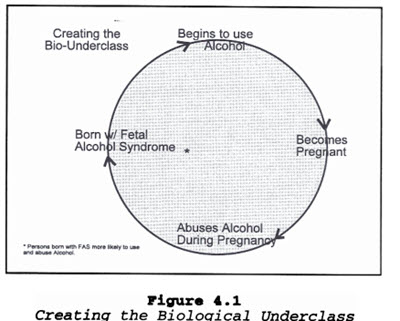

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome destroys the opportunity that is inherent in the "American dream." Individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome are mentally, emotionally, and psychological retarded. This retardation is biological and not related to environment.90 It is the behavioral and judgment problems that make FAS-affected persons likely to have children affected with FAS. Thus, a cycle of dysfunction is created with each generation of a family or a community affected more by FAS.' (See Figure 4.2).

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome destroys the opportunity that is inherent in the "American dream." Individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome are mentally, emotionally, and psychological retarded. This retardation is biological and not related to environment.90 It is the behavioral and judgment problems that make FAS-affected persons likely to have children affected with FAS. Thus, a cycle of dysfunction is created with each generation of a family or a community affected more by FAS.' (See Figure 4.2).

By not interrupting the cycle of FAS, society then is contributing to the creation of a biological underclass. To understand FAS as a community health issue it is necessary to distinguish community policy issues from the medical and legal issues.

The Inadequacy of the Medical Model

The standard medical model is an inadequate approach to solving the problem of FAS.' In the medical model, a physician takes a patient history, does a physical examination, makes a diagnosis, and prescribes treatment. The treatment either cures the patient--or not; at any rate the physician has fulfilled his or her responsibility.'

Yet, as predominant as the medical model is in the U.S. health care system, it is not without its weaknesses and faults. It is flawed because it focuses almost exclusively on the biological or psychiatric causes of illness while ignoring the political, social, and communal contexts in which health problems arise. It ignores factors, such as racism, social support, stress, and other elements of an individual's life-style, which are difficult to measure and even more difficult to treat. Because this medical-curative model ignores sociological causes of illness and disease, there is an inherent obstacle to taking a community preventive approach to solving the FAS problem.' While the medical model struggles to determine the impact of alcohol on a developing child, attempts to minimize the impact by encouraging pregnant woman not to drink during pregnancy, and attempts to find ways to treat FAS, it can not adequately address the prevention problem because it fails to focus on the sociological factors that contribute to women drinking during pregnancy. Without addressing sociological factors, no approach can be effective.

The Inappropriateness of Individual Rights Analysis

The law provides a similarly ineffective approach to FAS. The law's concern with fetal alcohol syndrome is limited to political interest in preventing fetal alcohol syndrome. The legal discussion focuses on the debtate between maternal rights and fetal rights. Most commentators want to resolve the issue of prevention of harm to the developing child based on whether the proposed activities interfere with maternal interests or promote fetal health." They view the primary question as "whether a pregnant mother has a legal, as well as moral, obligation to her unborn fetus?" Fetal rights advocates argue that a fetus has a protected interest in being born healthy.' According to fetal rights advocates, it is the responsibility of the state to protect the fetus from the mother's prenatal alcohol abuse.'

Maternal Rights Argument

Maternal rights advocates maintain that, although a pregnant woman may have a moral responsibility to protect the fetus, that obligation should not be translated into a legal responsibility. The maternal rights argument is basically centered around two major issues: control of maternal prenatal decision-making and protection of a woman's constitutional rights.

Control of maternal prenatal decision-making. Maternal rights advocates make several arguments for reserving absolute control of maternal prenatal decision-making to women. First, they argue that women are more affected by the consequences of prenatal decisions than anyone other than the fetus.' Second, women have better knowledge of their individual circumstances. Consequently, women, not the state, are in a better position to decide on appropriate prenatal conduct. Third, regulation of maternal prenatal conduct interferes with the rights of the parent to decide how to balance the interests of various family members.' Fourth, regulation of maternal prenatal conduct may subject the woman to the wishes of the father of the child.' Finally, regulation of maternal prenatal conduct "wrests from competent pregnant women the power to make decisions that affect their own bodies."

What concerns many maternal rights advocates is the potential unlimited expansion of fetal rights to cover "virtually every act of the pregnant woman." Articulated concerns about intrusions into the pregnancy include: "failing to eat properly, using prescription, nonprescription and illegal drugs, smoking, drinking alcohol, exposing herself to infectious disease or to work-place hazards, engaging in immoderate exercise or sexual intercourse, residing at high altitudes for prolonged periods, or using a general anesthetic or drugs to induce rapid labor during delivery.""I'' Maternal rights advocates see the pregnant woman in "constant fear. . . [of] a criminal prosecution by the state or a civil suit by a disenchanted husband or relative.

Protection of a woman's constitutional rights. Maternal rights advocates rely heavily on Roe v. Wade and cases such as Griswold v. Connecticut to assert that a pregnant woman has a right of personal autonomy, of bodily integrity,' and of parental autonomy." Furthermore, they maintain that constitutional guarantees of liberty and privacy limit a state's intervention in proscribing a pregnant woman's conduct."

Maternal rights advocates argue that fetal rights proponents cast women as nothing more than "incubators or containers" for their infants. Women, like men, are accorded constitutionally protected rights which a status, such as pregnancy, should not affect." According to maternal rights proponents, fetal rights arguments completely ignore the fact that a pregnant woman who abuses alcohol is not just potentially harming the fetus but is also harming herself. It appears that they fail to recognize the value of the woman's life. Maternal rights advocates ask why fetal rights advocates focus only on maternal behavior when it is only one factor which contributes to alcohol abuse by pregnant women. That is, why not focus on the social and economic conditions that contribute to alcohol abuse?

Maternal rights advocates see the granting of rights to fetuses as more of the same oppression, that is, a historical tradition of disadvantaging women on the basis of their reproductive capability." Thus, the state would not only restrict a pregnant women's autonomy, but also "define women in terms of their childbearing capacity, valuing the reproductive difference between women and men in such a way as to render it impossible for women to participate as full members of society.""

Maternal rights advocates argue that infringement on women's liberty would either discourage women from becoming pregnant or create an incentive for them to abort." Furthermore they maintain that granting rights to the fetus that can be asserted against the pregnant woman sets up an adversarial relationship between the woman and the fetus."

Slippery slope of regulation. Maternal rights advocates argue that because of Roe v. Wade," the fetus is not entitled to the constitutional rights of life and liberty." However, maternal rights advocates recognize that fetuses do have some rights under the law. It is the seemingly unlimited extension of rights against the pregnant woman that causes concern. For instance, some jurisdictions allow a child to have a cause of action against the child's parents for injuries that occurred prenatally; authorize the taking of custody of a child during pregnancy;" allow evidence of prenatal drug use to be considered during proceedings instituted by the state to take custody of a woman's newborn child; authorize a fetus to be considered a child under criminal child abuse statutes;" and require a pregnant woman to undergo refused medical treatment." Maternal rights advocates regard these existing intrusions against the mother as significant.

Judicial inadequacy in judging woman's circumstances. Maternal rights advocates also point out the inadequacy of the judicial response when addressing the problem of maternal alcohol abuse. As one commentator noted:

Although judges may order a pregnant woman to jail because her behavior may place her unborn infant at risk, judges do not order treatment centers to accept women and their children or Medicaid to cover the costs of treatment. Landlords are not ordered to keep them as tenants; obstetricians are not ordered to care for them; treatment centers are not designed with the needs of pregnant, addicted women and their children in mind; nor is the federal government ordered to fully fund maternal and infant health care and food programs.

A pregnant woman drinks because of "her economic status, her employment situation, her lack of access to prenatal care, her physical and mental condition prior to and during pregnancy, the demands of [family], whether her husband is supportive or abusive, and whether she was addicted to alcohol, drugs, or cigarettes prior to her pregnancy."' Given the many factors that contribute to a pregnant woman's behavior, some maternal rights advocates maintain that the judicial system cannot adequately evaluate the totality of the woman's circumstances." Thus, while maternal behavior may provide a credible basis for appearance of concern, in fact the government is unwilling to take effective and expensive efforts.

Interference with a woman's relationship with the health care system. Maternal rights advocates maintain that physicians cannot place the fetus' welfare above the woman's health. Nor can they be required to make "trade-offs" between a woman's health and the fetus' survival; giving fetuses rights to health will require just that.' In fact, maternal rights advocates argue that giving fetuses rights against the mother will turn doctors, nurses, and hospitals into "pregnancy police."' Fetal rights advocates counter that health care providers will no more become "pregnancy police" than pediatricians have become "child-rearing police" under statutes requiring the reporting of post-natal child abuse."

Fetal Rights Argument

Fetal rights advocates focus on the right of a child to be born healthy. Specifically, they argue that a child has a "legal right to begin life with a sound mind and body." Thus, according to the fetal rights advocates, a pregnant woman has a legal duty to create the best possible prenatal environment."

Protecting the health of the unborn child. Fetal rights advocates maintain that granting fetal rights is a legitimate and important purpose because it protects the health of the child." ' They argue that, since a mother would be subject to criminal sanction for imposing similar risks on a newborn, there are no persuasive justifications for not protecting the child during pregnancy.' Fetal rights advocates argue that there is little distinction between a fetus and a newborn.' In fact, some commentators are referring to a mother's conduct as "fetal abuse... Fetal rights advocates actually maintain that Roe v. Wade gives the fetus the right to be born healthy,'" and that the state must protect the fetus." According to this reasoning, prior to fetus viability, a woman may elect to have an abortion. After viability, the state has a compelling interest in potential life." Thus, after viability, unless the woman's life or health is threatened, the state may prohibit abortion. Furthermore, the argument goes, since alcohol use may result in spontaneous abortion, states with post-viability abortion statutes'may proscribe a pregnant woman's alcohol use to protect a viable fetus.` Similarly, since a state has a compelling state interest in "protecting potential life," the Roe viability standard arguably does not limit a state's intervention to simply the proscription of abortions.' Rather, implicit in this compelling interest is a "right to protect potential life from being unnecessarily injured."' Thus, according to fetal rights advocates, it is the responsibility of the state to protect the fetus from the mother's prenatal alcohol abuse.'

Lack of personhood not a barrier to fetal rights. Fetal rights advocates distinguish Roe v. Wade and subsequent abortion cases by arguing that the maternal privacy right at issue in abortion is on the woman's decision whether to continue her pregnancy, while in the fetal abuse context it's on the woman's conduct during her pregnancy.' Thus, according to fetal rights advocates, the state's interest in abortion focused on safeguarding the woman's health and protecting the fetus from intentional termination' does not conflict with the state's interest in enhancing a person's quality of life by protecting the fetus from harm."'"

While fetal rights advocates acknowledge that fetuses do not have fourteenth amendment rights, nevertheless they maintain that the provision of fetal rights is supported. For instance, they point to the right of a child to bring a civil law suit against a third person for prenatal injury6 43 including wrongful death actions, the right to inherit property, and the right of the state to bring criminal action because of intentional injury to a fetus.' In fact, some jurisdictions allow children to sue for prenatal injuries that are caused by the defendant's preconception negligence. Furthermore,. fetal rights advocates rely on the trend toward lifting interfamily tort immunity, thereby permitting suits by children against parents who have caused the child avoidable injury in support of holding a woman responsible for avoidable prenatal injury."

As to maternal prenatal conduct, a woman's constitutional rights are limited. Fetal rights advocates maintain that a woman's constitutional rights are limited with regard to the fetus and prenatal conduct. First, fetal rights advocates maintain even a woman's constitutional right to bodily integrity, which ordinarily would allow her to refuse medical treatment, is limited. In fact, courts have held that a person's right to refuse medical treatment can be superseded in order to protect dependent third parties, to preserve life, and to preserve the ethical integrity of the medical profession. Thus, courts have refused to sustain a pregnant woman's refusal of medical treatment where the decision will result in the abandonment of minor children. Even where the pregnant woman has no minor children, courts have relied on the state's interest in preserving life to consider the fetus an "innocent third party" deserving of protection. Some jurisdictions have held that a state's interest in the potential life of a fetus may outweigh any intrusion on the rights of a pregnant woman to refuse medical treatment. Thus, fetal rights advocates argue that, having waived her right to abortion, a pregnant woman has a duty to ensure that her fetus enters the world as healthy as possible's" and may not withhold medical treatment from the fetus."

Furthermore, fetal rights advocates argue that since even the fundamental rights" may be denied under certain circumstances, the state has the power to restrict alcohol use which is, at best, merely a privilege. Given the legitimate state interest in protecting fetal life and the tremendous cost to society of fetal alcohol injury, fetal rights advocates argue that the state's primary goal must be to protect the unborn child, even at the expense of infringing on maternal privacy and autonomy.'

In responding to maternal rights advocates who argue that pregnant women have a right to bodily control, fetal rights advocates maintain that a woman subordinates her right to control her body when she becomes pregnant and decides to carry the fetus to term. According to fetal rights advocates, the pregnant woman's interest in autonomy and bodily integrity must be balanced against the welfare of the fetus.' As one commentator argues: "a woman's right to abuse her own body and threaten her own health should not extend to the body of her fetus."'

Inadequacy of Both Fetal Rights and Maternal Rights Model for the Prevention of FAS

Both the fetal rights and maternal rights approaches are inadequate to prevent fetal alcohol syndrome. Both approaches ignore the cumulative impact that individual decisions have on the ability of a community to survive. Every community is dependent on the presence of a minimal level of functional adults. If individual decision-making diminishes the number of available functional adults in a community, the community will slip into dysfunctionality or die. Under such circumstances, it is hard to argue that over the long term the individual is impacted more significantly. Furthermore, the rights model ignores the fact that humans are communal beings and that communities, not individuals, are the cornerstone of society. As such the survival of communities cannot be left to individual decision-making.

Some persons may argue that it is the individual that has the most knowledge about her circumstances and, thus, is in the best position to make decisions for herself, the child, and the community. However, this argument assumes too much. Knowledge about individual circumstances does not necessarily translate into ability or motivation to act appropriately to protect herself, the child, or the community. Michael Dorris, in his testimony before the Senate in 1990, gave a perfect analogy:

A blind woman has a child by the hand, and in her attempt to cross a busy street, misjudges the traffic. The child is hit by a car and killed. We, the community, watch this tragedy and then move on, minding our own business. The next year, the woman does the same thing, and again, the child is hit and dies. Again, we look on, watch this happen for a second time, and continue to remain detached from the situation. We avoid getting involved to help her and her child by not even telling her when the light is green. How many women and children will be injured or die before help is offered? It does not solve the situation to blame the woman because she too is a victim—do we punish her for being blind? The answer is obviously no. Instead, assistance, support, and treatment are vitally needed to save her and her child.' (emphasis added)

No doubt efforts to "protect the community" will be disproportionately applied to poor women and women of color."' In a class-conscious and racist society, women with resources (white middle-class women) are able to buy their way out of having to conform. And in a racist society women of color are always a suspect class. Yet, this argument is disingenuous. In a racist society, it is the community that ends up supporting and caring for disenfranchised women. Yet, the maternal/fetal rights analysis would not only pit the woman against the fetus but the woman against her own interest and the interest of her community. A community health approach avoids having to make a choice based on rights and thus, minimizes, if not avoids, the whole adversarial relations entailed by a rights analysis.

Certainly, both fetal rights advocates' and maternal rights advocates' proposals contain components of a community health approach. The maternal rights advocate would focus on early prevention and the fetal rights approach would be more likely to deal with the recalcitrant woman. Nevertheless, both approaches are incomplete and therefore inadequate." The primary problem is that both approaches pit the mother and fetus against each other." Such an approach is not only negative, it is essentially unresolvable.20 As one commentator noted, "To present pregnancy as a conflict of rights between a woman and her fetus is entirely inappropriate. A fetus is as much a part of a woman as any part of her body, and to view them as being in conflict serves only to ignore this organic unity."" Constitutional law cannot truly protect a woman or the fetus by pitting them as adversaries.' If there is to be an effective protection of the woman, the fetus and the community, the legal analysis must shift from "an assumption of conflict to an acknowledgment of the interdependence of the maternal-fetal relationship."' The conflict model undermines the development of effective policy alternatives.'

Not only is a community health approach nonadversarial, it explicitly recognizes the inter-connectedness not only between the woman and the fetus but between the woman, the fetus, and the community.' A community health approach also resolves the resolution of the problem in the context of the unique socio-cultural needs of different communities.'

Distinguishing the Community Health Model

The community health model differs from both law and medicine. Unlike law and medicine, community health's primary focus is neither the individual nor an individual's rights or interest. Community health policy is concerned with protecting the public—the community as a whole. Except to the extent that improving individual health improves the community health, its primary concern is not individual health. A community functions only as well as the members of the community are healthy. Thus, the goal of community health is to assure optimal health for all its individual members.

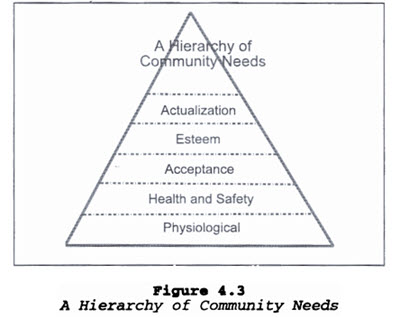

Since communities differ greatly, promoting the community's health has to be done within the context of the community's need. Just as Maslow defined the needs for individuals, every community has a sociological explanation of it needs and consequently its behavior.' Every community has several levels of needs:

Physiological Needs: This first level of community motivators includes such needs as hunger, clothing and personal comfort.

Physiological Needs: This first level of community motivators includes such needs as hunger, clothing and personal comfort.

Health and Safety Needs: This second level of community motivators includes health, security, protection, freedom from fear, anxiety and chaos, need for structure, order, law.

Acceptance Needs: This third level includes the need for the community to be accepted and to be recognized by the society at large.

Esteem Needs: The fourth level of the hierarchy focuses on the need for the community to be respected by others and to attain self-confidence, strength, a feeling of worth.

Community Actualization Needs: The fifth level of the hierarchy represents the highest level of fulfillment that communities can strive for; communities that reach actualization realize their full potential.' (See Figure 4.3).

In accordance with Maslow's theory, as individuals satisfy their own needs and come closer to actualizing their innermost potentials, they become increasingly devoted to the happiness of others. Self-actualized people use their potentialities for creative results that are beneficial to themselves and to society as a whole; they surmount the dichotomy between individual development and the common good. However, the functional level of a community is based on the resources needed to address an individual's basic needs. Thus, a minority of individuals in a community can determine the functional level of the community if that minority represents a significant portion of the community. Essentially, the functional level of a community is based on the lowest level of need that a significant portion of the community is still struggling to meet.

Thus, where a significant portion of a community is still struggling to meet their need for food, shelter, and clothing (i.e., the homeless community), the functional level of the community is at the physiological level. Similarly, where a significant portion of the community is struggling with issues of violence, drugs, illness, and death (i.e., inner city communities), the functional level of the community is at the safety and health level.

Community needs are hierarchical and the community's pursuit of a higher need is impaired until a lower need is substantially met. However, once lower needs are met, it is the higher unmet need that becomes the basis for motivation. Thus, identifying and helping a community to meet its unmet needs is essential not only to the survival of the community but to its growth and development as well.

The ultimate need that every individual has, and thus every community, is "actualization." Community actualization is the community's efforts to maximize its talents and resources--its effort to become all that it can. However, a community can't focus on actualization if its needs for food, clothing, shelter, safety, or health are not met. Rather, communities, like individuals, will focus on obtaining "lesser" unmet needs. Consequently, the focus of community health should be to see that the basic community need, a satisfactory level of health, is met. No community can become actualizing without health.

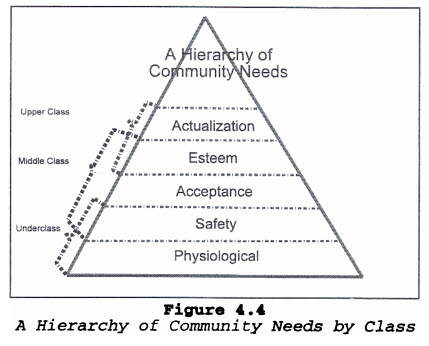

In a class-based society, we have communities that are functioning and competing on different need attainment levels. Many middle-class and upper-class communities' unmet needs are esteem and actualization. Individual rights and interests are necessary for individuals to become self-actualized and to develop strong esteem. Consequently, individual rights are also necessary for a community that is working to develop esteem and to become actualized. Thus, for many middle- and upper-class communities, protecting individual rights and interests is a prerequisite for their community's need fulfillment.

In a class-based society, we have communities that are functioning and competing on different need attainment levels. Many middle-class and upper-class communities' unmet needs are esteem and actualization. Individual rights and interests are necessary for individuals to become self-actualized and to develop strong esteem. Consequently, individual rights are also necessary for a community that is working to develop esteem and to become actualized. Thus, for many middle- and upper-class communities, protecting individual rights and interests is a prerequisite for their community's need fulfillment.

Underclass communities struggling to obtain food, clothing, housing, safety, and health and middle-class communities struggling to obtain acceptance may view the rights and interests arguments advanced by those seeking esteem and actualization of lesser importance. This is a very significant fact when considering the impact needs fulfillment has had on policy-making in medicine, law, and community health. Since most of the policy makers and providers are functioning at least at a middle-class needs level, and many of their communities are striving to become actualized, much of the discussion around problem-solving is centered on protecting rights or interests. The result is that the policy makers and providers filter the potential policy, law, or intervention through their own community need for esteem and actualization.

Certainly, individual rights and interests are important to all communities, but they should not be the primary focus for basic community health policy. It may be an appropriate part of the legal analysis and it is certainly an appropriate part of the political analysis, but the discussion must also include a community needs focus.

Of course, a major question becomes how will that community focus be actualized without infringing on individual rights? Frankly, as long as we continue to think of individual rights and community interests as dichotomous needs in conflict with each other, it is impossible to construct a solution. Community Health Interventions

To that end, then, we can now look at the traditional public health approach to promoting community health. Public health interventions can be classified as primary, secondary, and tertiary intervention. Primary intervention steps in and prevents disease entirely--the disease never happens and never occurs. For example, school vaccination, fluoridation of the community water, and sanitation efforts are all primary community health interventions.

Tertiary interventions are efforts to minimize the long-term effect of a disease. Tertiary intervention is not prevention. The disease or disorder has occurred; effort is directed at minimizing the effect. Tertiary intervention is treatment. The baby is here, we cannot stop fetal alcohol syndrome, how do we now deal with it, how do we now help that child affected by fetal alcohol syndrome? It is treating a problem that has not been prevented--a problem that exists because primary and secondary interventions were not effective. For example, diet and exercise will not prevent diabetes. Rather, these interventions will affect the impact of the disease on the individual and thus the community.

Many people tend to think of community health as prevention. But prevention is only one aspect. Treatment is an aspect since the community is just as affected by the diseases that go untreated as by those that go unprevented. So, though we can't prevent a disease, it is nevertheless appropriate to implement tertiary community health intervention.

Secondary interventions fall between prevention and treatment. These efforts are both to prevent the further development of the disease and to lessen the impact of the existing disease. For example, throat cancer is fairly curable if caught early.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Community Health Interventions

The focus on the community as opposed to the individual and the traditional community health approach to looking at disease begin to make sense when you look at fetal alcohol syndrome. The way to prevent fetal alcohol syndrome is for the person to never start drinking alcohol, or to stop drinking alcohol before pregnancy. Efforts targeted at achieving those goals are primary interventions. Secondary intervention is for the pregnant woman to stop drinking as early as possible during pregnancy. Tertiary interventions are those activities that we do after the child is born.

Educational programs, notices of warning about drinking during pregnancy, doctors asking routine questions on drinking and educating their patients individually are all ways to prevent fetal alcohol syndrome. These kinds of activities are perfectly well- suited for the community health model mode and require mainly funding, a change of attitude by doctors, legislation requiring alcohol distributors to put notices on bottles, and requiring people who serve alcohol to provide warnings so that pregnant women will know that drinking is harmful to health.

Secondary prevention activities include education by the individual health care provider, intense counseling, and access to drug treatment programs. There are three problems with getting the problem drinker in drug treatment. First, if they are not in prenatal care, the health care provider can't assess their alcohol use, educate them, or make appropriate referrals. Yet, as important as prenatal care is, it is important for us to remember that prenatal care in itself does not prevent fetal alcohol syndrome.

Since many pregnant women willingly undergo significant behavior changes for the benefit of their developing child, the educational and drug treatment referral component of prenatal care is particularly effective. The problem with education is that it has little or no effect on problem- addicted drinkers. Their addiction gets in the way of their judgment. Because of their addiction, education is not enough for some women to interrupt their problem drinking. They need access to drug and alcohol addiction programs.

Access to drug and alcohol treatment programs presents several problems. First, most drug and alcohol addiction programs are built around a male mode. Women need treatment models based on social support. Second, many drug and alcohol treatment programs won't take pregnant women. Thus, both primary and secondary interventions will require at a minimum additional funding and additional funding presents conflicts with the majority group's actualization of needs.

In our society, we have articulated actualization as non-interference in both personal interests or property interests. Our ability to take our personal resources and property resources and use them in whatever way we see fit for ourselves is self-actualization. Interference with that is unacceptable. To get the kind and quantity of treatment centers that are needed necessarily implies some interference in property rights.

In part, fetal rights arguments may be motivated by a desire to "correct" the problem with minimum interference in property rights. For example, a clearly criminalization argument represents a desire to impact the fetal alcohol problem with minimal infringement on property interests. Expanding the existing criminal system would probably be less expensive than developing an intensive network of clinics and treatment centers specifically designed for pregnant women. Criminalization places the burden entirely upon the woman and presents the aura of working on fetal alcohol syndrome while at the same time protecting property interests. However, it is a false aura. First, criminalization of behavior has been ineffective in other areas. Murder laws have not prevented murder. There is no reason to believe that criminalization of alcohol use and drug use during pregnancy will be effective. Furthermore, property interests are not protected since presumably additional jails will have to be constructed.

Maternal rights advocates apparently are not as interested in protecting property interests since they promote more funding for prenatal and treatment centers. This will require funding. Maternal rights advocates promote access prenatal care as the way to deal with fetal alcohol syndrome. In the same way that the fetal rights people are looking at self- actualization, so are the maternal rights people. This actualizes individual interests. They want to work on the problem, but they do not want their individual interests interfered with. Their approach will in many ways be effective since prenatal care and education will take large groups of women out of the group of recalcitrant patients. However, the maternal rights groups are similarly in error. Inherent in their argument is a willingness to accept a certain amount of fetal alcohol syndrome babies to protect individual rights.

Community health policy, however, does not approach the solution as an either-or dichotomy. Community health policy accepts primary intervention that includes education, secondary prevention that includes pre-intervention such as prenatal care, and tertiary prevention which includes a mechanism to force people who are unwilling to obtain care. Community health policy then says that all three of these are appropriate and necessary and that no one or two alone are effective.

Responsibility, Caring, Interdependency and Contextual Reality

My friend just adopted two little boys: Daniel (age 6) and Thomas (age 5) with fetal alcohol effect. Their biological mother has two other children:* Marie (age 3) and Erik (age 2) with fetal alcohol syndrome. Both of those children have been placed for adoption. She received no prenatal care during her pregnancy with Daniel. Although on welfare, she received no prenatal care during the pregnancies with Marie and Erik. After Daniel's birth, she was visited by a community health nurse who discussed the effect of drinking during pregnancy. At her prenatal visits, she was encouraged to obtain alcohol addiction treatment. She is now pregnant with her fifth child.

The issue here is not one of "rights" but of responsibility, caring, interdependency, and contextual reality. When posing the problem as one of rights, that is rights of the fetus versus rights of the mother, a win-lose situation is necessarily being constructed. A focus on the rights of the fetus, for instance, completely ignores the responsibility that the society has for the mother's situation. The argument ignores society's responsibility for correcting the imbalance. The drug-abusing mother has been socially and sometimes biologically deprived. Without access to education, health care, housing, and good parenting, the mother is not solely responsible for her drug and alcohol abuse. Furthermore, there is a real and justified fear of how society may use the "rights of fetuses" to control women.

On the other hand, the "rights of the woman" argument ignores the biological interdependency of the unborn. It will be little comfort to a FAS girl to know that she has certain rights when she lacks the biological capabilities to make full use of those rights. As the saying goes, rights won't keep you warm. In this society, where merit is supposed to be the basis for all rewards, a person who is born either legally or biologically handicapped cannot make any significant achievement based on merit. Thus, there is an inherent hypocrisy in saying that a person has a fundamental right of privacy and liberty, that a person's rewards are determined on their ability, but that the society will not step in to prevent a known legal or biological disability.

"Responsibility" analysis provides an alternative to the "rights" analysis. Under this analysis, it is necessary not only to analyze the individual's responsibility but the society's and community's responsibilities. What are the society's responsibilities toward the drug/alcohol abusing woman? If we care for the woman, what is necessary for us to help her? At the same time, we acknowledge that the fetus has an interdependence on women and society. That interdependence requires us, individually as women and as a society, to do what we can to assure every child is born healthy. The ability of a person to succeed and lead a productive life is directly dependent on how well we meet our responsibilities. A sense of caring and interdependency dictates that we look beyond a win-lose "rights" analysis.

The rights issue historically and constitutionally, has been the framework on which we have to justify our decisions. However, it should not and cannot be the sole basis for continuing decision-making. Evidence that the rights analysis can be a bankrupted analysis is provided by the use of this analysis in the past to legally subject Blacks and women to White males. It is an analytic framework based on domination, hierarchy, and patriarchy. In the twenty-first century we must move to develop a legal framework based on responsibility, caring, interdependency, and contextual reality. In the case of fetal alcohol syndrome, we must recognize that the pregnant woman has a responsibility to the unborn fetus and the community to prevent harm; that the community has to care enough to assure complete access to the full range to preventive services; that the woman, the fetus and the community are interdependent; that you can't address the issues of one without addressing the issues of the others; and, finally, that the reality is that not all communities are the same and any solution has to be flexible enough to accommodate the full range of communities.