Become a Patreon!

Abstract

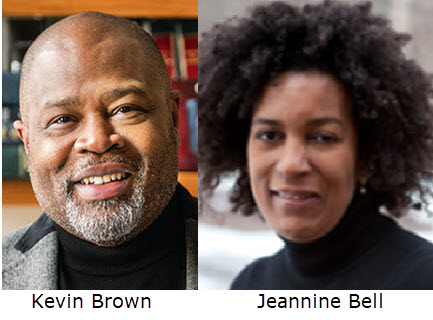

Excerpted From: Kevin Brown and Jeannine Bell, Demise of the Talented Tenth: Affirmative Action and the Increasing Underrepresentation of Ascendant Blacks at Selective Higher Educational Institutions, Ohio State Law Journal 1229 (2008) (230 Footnotes) (Full Document)

Selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs first created affirmative action admissions policies in the late 1960s and early 1970s. At that time, due to the historical impact of racism on American society, the “one-drop rule” classified any person with some African ancestry as black. The predominance of the one-drop rule meant that children born from black and white parents were brought up to consider themselves black. In addition, a very small percentage of blacks of college age-and thus potential beneficiaries of these admission policies-had a foreign-born black parent. As a result, at this time the general rule about the overwhelming majority of blacks who were of college age was that they were descendants of blacks originally brought to the United States as chattel slaves. This was a fundamental assumption upon which affirmative action was developed.

Selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs first created affirmative action admissions policies in the late 1960s and early 1970s. At that time, due to the historical impact of racism on American society, the “one-drop rule” classified any person with some African ancestry as black. The predominance of the one-drop rule meant that children born from black and white parents were brought up to consider themselves black. In addition, a very small percentage of blacks of college age-and thus potential beneficiaries of these admission policies-had a foreign-born black parent. As a result, at this time the general rule about the overwhelming majority of blacks who were of college age was that they were descendants of blacks originally brought to the United States as chattel slaves. This was a fundamental assumption upon which affirmative action was developed.

Supporters and critics hailed Grutter v. Bollinger, the Supreme Court's most recent higher education affirmative action decision, as a victory for affirmative action. By solidifying support for affirmative action, both supporters and critics must have envisioned the maintenance of an established presence of blacks whose racial and ethnic ancestry was deemed as predominantly traceable to the historical oppression of blacks in the United States-at least for the next twenty-five years. Yet, despite the Supreme Court having upheld university affirmative action admissions plans, right now we are witnessing a historic change in the racial and ethnic ancestry of blacks who are the beneficiaries of affirmative action. Selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs are admitting increasing percentages of blacks with a white parent and foreign-born black immigrants and their sons and daughters. In light of this dynamic, a change is occurring in the once-general rule regarding the racial and ethnic ancestry of blacks on affirmative action throughout the country. As a result, blacks whose predominate ancestry is traceable to the historical oppression of blacks in the United States are likely more underrepresented in affirmative action than most administrators, admissions committees, or faculties may realize.

This Article will question the process that lumps all blacks into a single-category approach that pervades admissions decisions of so many selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs. In directing attention to the changing racial and ethnic ancestry of blacks on college campuses, we describe the significant increase in the percentage of blacks with a white parent and foreign-born black immigrants and their sons and daughters on college campuses. As authors, we are mindful of the long and odious history in the United States of classifications based on ancestry. We are cognizant that discussions about the underrepresentation on affirmative action programs of particular blacks as determined by their parentage within the “black” category cannot help but dredge up negative feelings from this infamous past. Beyond generating negative feelings, the phenomenon we are describing is counterhistorical. Historically, the black experience is the treatment of black individuals as members of one race. This treatment produced a cultural orientation for blacks in the United States centered on the fundamental belief in a unified black population. Discussions about the racial/ethnic parentage of blacks require the recognition and open discussion of the existence of various “black” racial and ethnic groups. As a result, such discussions call into question black unity, which is the historical core belief of the black community. Nevertheless, we proceed, mindful of the reality that not discussing the growing percentage of blacks with a white parent and foreign-born black immigrants and their sons and daughters among blacks on affirmative action is a choice. It means that blacks whose predominate racial and ethnic heritage is traceable to the historical oppression of blacks in the U.S. are far more underrepresented than administrators, admissions committees, and faculties realize. As a result, they are far less likely in the future to qualify for the positions of social advantage awarded to those who obtain selective academic credentials based on them. In this situation, our silence would constitute our assent to these developments.

An overarching vision of the goals of affirmative action-at least as it applies to the black community in the United States-is required in order to express concern about the growing underrepresentation on affirmative action of blacks whose predominate ancestry is traceable to the historical oppression in the United States. In this Article, we approach affirmative action from the perspective of the historical struggle undertaken by the black community to overcome its racial oppression in the United States. Affirmative action is, therefore, a part of the strategy for the uplift of the black community in the United States. W.E.B. Du Bois, the legendary African-American social commentator, articulated this concept over a hundred years ago in his famous article The Talented Tenth. Du Bois's view squarely places part of the responsibility for black empowerment gained through college and university attendance on the shoulders of the Talented Tenth. The Talented Tenth are the well-educated, distinguished men and women crusaders dedicated to alleviating the burdens of blackness and the color line. According to Du Bois, members of the Talented Tenth are obligated to sacrifice their personal interests in an effort to provide leadership to improve the social, economic, and political conditions of the black community.

This Article is organized in the following manner: after clarifying the different groups of individuals who comprise the black population on college and university campuses, Part One of the Article explores the purposes of affirmative action, focusing particularly on the policy's theoretical and historical roots as a remedy for historical discrimination in the United States. In this vein, we argue that affirmative action is intended to assist in the attenuation of the historical effects of racial subordination of African Americans in the United States. This part also demonstrates that classifying blacks based on their racial/ethnic ancestry, with a focus on attenuating the effects of racial subordination in the United States, is consistent with the Supreme Court's opinion in Grutter. Part Two focuses on the increasing percentage of blacks with a white parent and foreign-born black immigrants and their sons and daughters attending colleges, universities, and graduate programs, including the selective ones. Part Three discusses the implications of these demographic changes for the historical struggle against racial oppression in the United States. Part Four proposes a solution for administrators, admissions committees, and faculties of selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs.

[...]

Selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs first created affirmative action admissions policies in the late 1960s and early 1970s. There can be little question that the primary anticipated beneficiaries of these programs were blacks who were descendants of those brought to the United States in chains. At the time of the adoption of affirmative action plans, the racial and ethnic makeup of blacks in the United States was very different. The overwhelming majority of married blacks were married to other blacks. In 1960, only about 1.7% of married blacks had a white spouse. In addition, in 1960, less than 1% of the black population was foreign-born, totaling just 125,000 individual. As a result, a very small percentage of college-age blacks-and thus potential beneficiaries of these admission plans-had a foreign-born black parent. Due to the historical impact of racism on American society, the “one drop rule” classified any person with some African ancestry as black. Because of these realities, the general rule in American society about racial and ethnic ancestry of the overwhelming majority of college-age blacks-and thus potential beneficiaries of affirmative action-was that they were descendants of blacks originally brought to the United States as chattel slaves. This was a fundamental assumption upon which affirmative action was developed.

Supporters and critics of the Supreme Court's decision in Grutter must have envisioned the maintenance of an established presence of those whose racial and ethnic ancestry was deemed as predominantly traceable to the historic oppression of blacks in the United States-at least for the next twenty-five years. Yet, selective college, university, and graduate programs are admitting increasing numbers of Black/White Biracials and Black Immigrants. In light of this dynamic, we are witnessing a historic change in the general rule regarding the racial and ethnic ancestry of blacks on affirmative action throughout the country. There is increasing evidence that the underrepresentation of Ascendants admitted to selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs is far greater than administrators, admissions committees, or faculties realize.

In this Article, we questioned the lumping of all blacks into a single category approach that pervades admissions decisions of so many selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs in order to call attention to the growing underrepresentation of Ascendants on affirmative action. In order to draw distinctions among blacks for purposes of admissions to selective higher education programs, there must be an overarching vision of the goals of affirmative action-at least as it applies to the black community in the United States. We approached affirmative action from the perspective of the historical struggle undertaken by the black community to overcome its racial oppression in the United States. Affirmative action would be a part of the strategy for the uplift of the black community in the United States. W.E.B. Du Bois, the legendary African-American social commentator, articulated this concept over a hundred years ago in his famous article, The Talented Tenth. Du Bois's view squarely places part of the responsibility for black empowerment gained through college and university attendance on the shoulders of the Talented Tenth-well-educated, distinguished men and women crusaders dedicated to alleviating the burdens of blackness and the color line. According to Du Bois, the Talented Tenth was obligated to sacrifice their personal interests in an effort to provide leadership to improve the social, economic, and political condition of the black community. We also proposed a solution for administrators, admissions committees and faculties of selective colleges, universities, and graduate programs to address the growing underrepresentation of Ascendants.

As authors, we are mindful of the long and odious history in the United States of classifications based on ancestry. We are cognizant of the fact that discussions about the underrepresentation in affirmative action programs of particular blacks as determined by their parentage within the “black” category cannot help but dredge up negative feelings from this infamous past. Beyond generating negative feelings, the phenomenon we are describing is counter-historical. Historically, the African-American experience is the treatment of black individuals as members of one race. This treatment produced a cultural orientation for blacks in the United States centered on the fundamental belief in a unified black population. A discussion about the parentage of blacks for purposes of affirmative action requires the recognition and open discussion of the existence of various “black” racial and ethnic groups. As a result, such a discussion calls into question black unity, which is the historical core belief of the black community. Nevertheless, we proceed, mindful of the reality that not discussing the growing percentage of Black/White Biracials and black immigrants among blacks on affirmative action is a choice. Ascendants are far more underrepresented than many administrators, admissions committees and faculties realize. As a result, they are far less likely to qualify for the positions of social advantage in the future awarded to those who obtain selective academic credentials based on them. In this situation, our silence would constitute our assent to these developments.

Kevin Brown is Professor of Law, Harry T. Ice Faculty Fellow of Indiana University School of Law-Bloomington, and Emeritus Director of the Hudson and Holland Scholars Program at Indiana University-Bloomington. B.S., 1978, Indiana University; J.D., 1982, Yale University.

Jeannine Bell is Professor of Law and Charles L. Whistler Faculty Fellow, Indiana University School of Law-Bloomington. A.B., 1991, Harvard College; J.D., 1999, Ph.D. (Political Science) 2000, University of Michigan.

Become a Patreon!