Become a Patreon!

Abstract

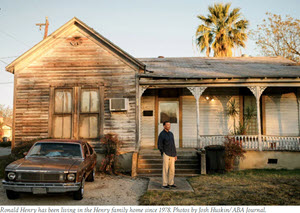

Excerpted From: Matt Reynolds, How Jim Crow-era Laws Still Tear Families from Their Homes, 107-MAR ABA Journal 52 (February/March, 2021) (Full Document)

Back in the late 1990s, Thomas Mitchell was an LLM student at the University of Wisconsin Law School researching land law policy when almost by accident, he stumbled across a little-known legal loophole that had stripped generations of Americans of their land.

Back in the late 1990s, Thomas Mitchell was an LLM student at the University of Wisconsin Law School researching land law policy when almost by accident, he stumbled across a little-known legal loophole that had stripped generations of Americans of their land.

Mitchell was volunteering for a legal organization and observing a meeting of Black farmers in a hotel conference room in Durham, North Carolina. They were engaged in a heated discussion about the class action settlement in Pigford v. Glickman, a case filed in 1997 against the U.S. Department of Agriculture alleging discriminatory lending that resulted in a consent decree awarding more than $1 billion to thousands of Black farmers. It was the largest civil rights settlement in U.S. history.

At the meeting, someone identified Mitchell as a lawyer. Before long, several people had regaled him with tales of how they had been stripped of the land they had inherited.

Two members of the same family explained how they had lost about 200 acres after another relative with a small stake had sold their share to a speculator who forced a partition sale. The land had been in the family since the late 1800s.

At first, Mitchell dismissed what he was hearing as a lack of sophistication about how the legal system works.

“What they had just described to me, I had never heard it before when I was in law school. No property textbook guide talked about the process working out that way,” Mitchell remembers.

His interest, however, was piqued. He politely promised to look into the matter, but when his research came up short, Mitchell contacted the family and asked to see the court records in their case.

He was stunned to discover the documents mirrored exactly what they had told him.

“It was like a fire sale,” says Mitchell, now a Texas A&M University School of Law professor who received a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” in 2020 for his work in property law.

At first, Mitchell thought the family's case might be the exception rather than the rule. Then he started looking at laws in all 50 states and realized he had just scratched the surface. The case was the catalyst for his effort to spotlight an inequity in property law that strips landowners, often the poor and people of color, of their equity and wealth. Heirs' property ownership, a subset of tenancy-in-common ownership, affects owners who share an interest in land, a home or a farm that is often transferred without an effective deed or will.

Heirs' property is considered a vestige of the Jim Crow South, where unsophisticated property owners without the means or ability to hire a lawyer-- or with a justifiable distrust of the courts--divvied up their assets informally, creating “interests” for descendants.

Regressive laws allow speculators to swoop in, exploit fraught family dynamics and fractionalize shared ownership through forced partition sales, divesting generations from lawfully owned property.

“The original sin is many of these families, when they first got the property in the late 1800s, tried to get a lawyer, but no lawyer would represent them,” explains Mitchell, who has been the driving force for heirs' property reform as principal drafter of the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, which offers greater protections to land and property owners entangled in court-ordered sales. “As a result, they fell into this heirs' property, which I almost think of as a Jim Crow form of ownership, and now they're trapped in it because they couldn't get 99% of their family to agree. I just think that's fundamentally unfair.”

There has been a landslide of property loss in the Black community since Reconstruction through violence, threats and intimidation, discriminatory lending, foreclosures, tax sales and legally sanctioned takings.

[. . .]

Kohanowski says it remains to be seen how effective the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act is in curtailing predatory developers and investors. He says homeowners are still vulnerable but that the law at least “levels the playing field” by giving heirs the right of first refusal and the chance to secure financing to buy out a competing interest. Kohanowski says the law in New York state also has an alternative dispute resolution component to help heirs settle disputes.

“My feeling is it's going to discourage this sort of investment activity and give us more tools to preserve intergenerational wealth, especially in communities of color,” Kohanowski says.

Become a Patreon!