Abstract

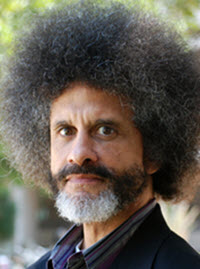

Jody Armour, Nigga Theory: Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity in the Substantive Criminal Law, 12 Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law 9 (Fall, 2014) (162 Footnotes)

Po' niggers can't have no luck-

Nigger Jim, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Some will find the N-word in my title jagged-edged and hurtful. Words can wound: more than mere vehicles for the expression of ideas or the transfer of information, words are deeds-acts with consequences-and the words “nigger” and “nigga” are two of the most violent and blood-soaked verbal acts in the English language. Nevertheless, used with the precision and reticence of a surgeon's hands, these vicious epithets can also suture the places where blood flows.

Some will find the N-word in my title jagged-edged and hurtful. Words can wound: more than mere vehicles for the expression of ideas or the transfer of information, words are deeds-acts with consequences-and the words “nigger” and “nigga” are two of the most violent and blood-soaked verbal acts in the English language. Nevertheless, used with the precision and reticence of a surgeon's hands, these vicious epithets can also suture the places where blood flows.

In that spirit, in profane language picked for its unparaphrasable power to focus attention on the implications of moral condemnation for racial justice and political solidarity, I use these jagged epithets here as part of a metaphoric redescription, in racial terms, of the criminal law's ancient subjective culpability or mens rea requirement. In this essay, in other words, a “nigga” is a metaphor for black wickedness, black mens rea, which I will use to probe the intersection of morality, race, and class in matters of blame and punishment and politics. An example of a non-racialized metaphor for mens rea would be the common law's “depraved heart” test of murderous mens rea in cases of unintentional homicide-the jury is given the depraved heart metaphor and told to use it as the litmus test for serious subjective culpability. From the standpoint of this ancient heart metaphor for moral blameworthiness, a “nigga” metaphorically is a depraved or indifferent black heart; but on another level, my metaphorical redescription of black subjective culpability and black mens rea in terms of “niggas” will be an urgent political call to bond with and support black-hearted wrongdoers.

To that end, this essay proceeds as follows.

I begin in Part I expounding on the inadequacy of our current legal and moral vocabularies and my repurposing of the words “nigger” and “nigga” to engage in an oppositional discourse I call “nigga- talk.” I use “nigga-talk” to help explain and problematize the need to distinguish, even within the black community, law-abiding, respectable blacks from so-called “niggas,” or morally deficient and contemptible blacks. In short, there exists a type of Black Criminal Litmus Test.

Part II elaborates on this litmus test by discussing what I coin “Good Negro Theory,” the constellation of assumptions, beliefs, and values that undergird the bad nigga-good negro dichotomy and its contention that law-abiding blacks should distance themselves from bad niggas. Part II also advances “Nigga Theory,” an argument aimed at eradicating the distinction between blacks and promoting solidarity between law-abiders and law-breakers regardless of race.

I return to this core aspect of Nigga Theory in Part III, which discusses our retributive urge, causation, and our general denial of accountability.

I. On Language, “Niggas,” and the Black Criminal Litmus Test

I first “dropped the N-bomb” at a Criminal Justice and Race Workshop for the Association of American Law Schools [AALS] during the 1999 Annual Meeting in New Orleans. In the company of sedate legal scholars, I performed an N-word-laden gangsta rap song by Ice Cube titled The Nigga Ya Love to Hate, spitting lines like “kicking shit called street knowledge-why more niggas in the pen than in college?” I told my audience that the baffling silences our professional vocabulary could not fill compelled me to use this profane alternative rather than iterate the voice of speechlessness underneath the rigor, precision, and eloquence of our scholarly marks and noises.

As criminal law professors, our primary professional vocabularies are those of morality and law-the two language games prosecutors and defense lawyers must master and deftly deploy-and thus I have thought a lot about the world of shared meanings these vocabularies create and what limits they impose; what can be done by one who speaks them and what cannot. As the son of a black prison inmate given 22 to 55 years for possession and sale of marijuana, and as a close friend of many black inmates, I would characterize my relationship with the language of blame and punishment inside and outside my law school classrooms over the past twenty years as impossible, for I find the proud but calcified language of both the legal academy and conventional morality-“choice,” “free will,” “personal responsibility,” “subjective culpability,” “malice,” “malignant heart,” “moral agency,” and “mens rea”-not adequate to my needs and purposes, to my sense of myself and my world, requiring me, as it plainly does, to view as wicked and irresponsible my closest friends, family, and the up to 90% of young black men in some inner city neighborhoods who will end up in jail, on probation, or on parole at some point in their lives. For me, any language whose words and logic lock up staggering numbers of truly disadvantaged black men on the ground of their own moral deficiencies is a disabled and disabling device for grappling with meaning in moral and criminal matters, one that ignores or discounts savage inequalities in race and class and sweeps empirically demonstrable anti-black bias under the rug of jury verdicts and “findings of fact” about guilt and innocence. Prevailing legal and moral language organizes and claims a meaning for experience in a way that blocks the access of “wicked” black wrongdoers to the empathy, sympathy, care and concern of ordinary, law-abiding people; such language actively stalls conscience in relation to such wrongdoers' suffering, masking the pity and waste of mass incarceration and draconian punishment. Yet in my scholarly associations and legal journals, I see an entrenched moral and legal vocabulary content to admire its own paralysis, to accept with serenity its estrangement of underprivileged and disadvantaged masses.

As James Boyd White points out, when words lose their meaning, a speaker must make a new language, remake an old one, or radically repurpose old words to serve new ends. In my N-word-laden 1999 AALS performance of Amerikkka's Most Wanted, I radically reconstituted my cultural resources-my possibilities for making and maintaining meaning-to make them adequate to my needs. Specifically, I repurposed “nigger” and “nigga” as terms of art in an oppositional discourse I shall call “nigga-talk.” Nigga-talk uses this “troublesome” word-a word Professor Randall Kennedy rightly calls the “nuclear bomb of racial epithets” in his 2002 book Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word its most condemnatory sense for conceptual purposes and in its most compassionate sense for political purposes.

Conceptually, nigga-talk uses the “morally deficient black man” sense of “nigga” to critique the categories, distinctions, and dichotomies of conventional morality and the substantive criminal law.“Nigga” in this sense means precisely what black comedian Chris Rock means in his famous laugh line, “I love black people, but I hate niggas!”, where lovable “black people” means “law-abiding, respectable blacks” and “niggas” means morally deficient and contemptible black criminals. As White points out, jokes, like all texts, are invitations to share the speaker's response to the world which we accept through our laughter, and implicit in Rock's joke is a political invitation to distinguish between a law-abiding and respectable “us” and a morally contemptible “them,” an invitation to niggerize-or niggarize-black wrongdoers, which black audiences in packed auditoriums heartily accepted through peals of laughter and a chorus of “amens,” “uh-huhs,” and “preach!” Part moral mantra, part political slogan, part sneering closing argument refrain, the phrase “I love black people but I hate niggas!” struck a resonant chord with black audiences because many do view black wrongdoers as morally condemnable “niggas.” No utterances in the English language more forcefully drive a political wedge between a worthy “us” and an unworthy “them” than this vile epithet-none more bluntly express and inflame that widely shared and deeply entrenched urge, to put it crudely, to retaliate and avenge, or, to dress it up in loftier language, to “return suffering for moral evil voluntarily done” or to act on “the necessity of purging one's own country from depraved criminals” or to see blameworthy wrongdoers “‘pa[y] one's debt’ to society.” Legal philosopher Meir Dan-Cohen aptly dubs this urge to blame and punish wicked wrongdoers “the retributive urge.” Because millions of Americans of all races share that laughing black audience's contempt for black wrongdoers, so-called “niggas” inflame the retributive urge in millions of all races.

Rock's blunt moral distinction between respectable “black people” and damnable “niggas” parallels the more genteel one asserted by Professor Randall Kennedy between what he calls law-abiding “good Negroes” and criminal “bad Negroes.” Specifically, Kennedy exhorts good law-abiding blacks to “distinguish sharply between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Negroes” for the sake of safety and racial respectability. His litmus test for “bad Negroes” is identical to Rock's for “niggas”-namely, criminal wrongdoing. In support of his distinguish-and-distance-them-from-us approach, Professor Kennedy cites black civil rights icon Thurgood Marshall. As Kennedy points out, Marshall, working on behalf of the NAACP, initially allowed it to represent only good-“innocent” For example, Marshall refused to represent a sixteen year old black boy sentenced to death for rape and attempted prison escape on grounds that “the youngster was ‘not the type of person to justify our intervention.”’ Recast in Rock's street vernacular, Thurgood Marshall sharply distinguished and distanced the interests of “black people” from those of “niggas.” According to Professor Kennedy, even when Marshall later “loosened his policy” and represented some black defendants he believed to be guilty, Marshall's worries about black people's respectability in the eyes of whites kept Marshall from ever “tak[ing] the position that racism excuses thuggery when perpetrated by blacks.” So the distinguished black scholar, the venerable black Supreme Court Justice, and the iconic urban comedian converge on the Black Criminal Litmus Test of condemnable blacks, differing only in whether they call these morally odious creatures “niggas” or “bad Negroes” or “thugs.” Accordingly, I will use the terms “niggas,” “niggers,” and “bad Negroes” interchangeably and in contradistinction to their loveable and respectable polar opposites-“black people” and “good Negroes.” In sum, at the conceptual level I use these terms in their most morally judgmental and retributive-urge-inflaming sense to first pinpoint, then discredit moral condemnations of black criminals. I discredit them both on reliability grounds, given the pervasiveness of “unconscious bias,” and on legitimacy grounds, given the simple reality of “moral luck.”

The reliance on mens rea in deciding criminal culpability has analogues here. Prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges and jurors routinely debate and weigh the moral blameworthiness of wrongdoers because the substantive criminal law directs them to under the ancient legal maxim, actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea-in Blackstone's translation, “an unwarrantable act without a vicious will is no crime at all.” Under this mens rea principle, it is unjust to punish someone who commits an “unwarrantable act”-i.e. a wrongdoer he acted with a “vicious” or wicked will. As the Model Penal Code puts it, “[c]rime does and should mean condemnation.” Thus, under the mens rea principle, if jurors conclude that a wrongdoer killed someone without the requisite subjective wickedness or “vicious will,” they must return a verdict of not guilty. So the criminal law-through its mens rea requirement-routinely directs judges and jurors to morally distinguish between wicked and innocent wrongdoers and to differentiate degrees of wicked criminality for purposes of punishment. Under the law of homicide, for instance, a wrongdoer can suffer different punishments depending on whether he is found wicked in the 1st or 2nd Degree; voluntarily or involuntarily wicked; purposely, knowingly, recklessly or negligently wicked; or wickedly depraved and indifferent. Correspondingly, under the Black Criminal Litmus Test championed by proponents of a politics of respectability in criminal matters like Kennedy and Rock, a jury could find a morally blameworthy black wrongdoer to be a “nigga” in the First or Second Degree, a Voluntary or Involuntary “nigga,” a purposeful, knowing, reckless, or negligent “nigga,” or a “nigga” with a depraved and malignant heart. In fact, most “official niggas” (i.e., blacks formally convicted of a crime) have been found subjectively wicked in one of these ways beyond a reasonable doubt by a jury or other fact finder, so criminal conviction provides assurance-backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. criminal justice system-that only black wrongdoers who deserve our most corrosive contempt achieve the status of felonious “official niggas.”

Politically, a key insight of the law and literature movement is that the true center of value of a word, text, or performance of language, its most important meaning, is to be found not in any factual information that it conveys-not in what is says-but in what it does, specifically, in the community that it establishes with its audience. “It is here,” says James Boyd White, “that the author offers his reader a place to stand, a place from which he can observe and judge the characters and events of the world . . . .” The place I offer my reader to stand through the many repetitions and juxtapositions and performances of the “N-word”-a place made solid by my substantive, conceptual uses of the term to pinpoint unwarranted moral condemnation one beyond such condemnation, one from which it can be seen that a person's self is a tissue of contingencies whose moral record is determined by the union of fortuity and human frailty rather than mere “free will.” It is a place that prioritizes compassion, concern, and mercy over retribution, retaliation, and revenge. Hence, it is a place from which disproportionately poor black criminals can be understood as tragic social facts for which we as a class and race-driven nation are accountable, rather than as wicked wrongdoers mired in self-destruction for which they alone are to blame. Accordingly, I use the N-word in this essay as a brush stroke in a new political landscape, one in which the very meaning of the word-its substantive content and range of application-is part of a fierce contest over the “us” and “them” of politics, over the formation and transformation of individual and collective black identities.

Allow me to go a step further. Politically conscious black urban poets and N-word virtuosos-The Last Poets, Tupac Shakur, dead prez, Nas, NWA, Ice Cube, Jay Z-vividly illustrate how people use words, sometimes the very same word, to embrace or push away, recognize or deny, others. In the hands of these poets gangsta rap is N-word laden oppositional political discourse; for them “nigga talk” is language smitheryed to challenge conventional characterizations of black criminals with ironies, inversions, and invitations to bond with them. These oppositional black poets provide the inspiration for my metaphoric redescription of mens rea and moral blame in terms of the N-word. After all, as Richard Rorty observes in his philosophical essays on language through the lenses of Wittgenstein, Davidson, and Nietzsche, viewing human history as the history of successive metaphors lets us “see the poet, in the generic sense of the maker of new words, the shaper of new languages, as the vanguard of the species” and of revolutionary science, morality, and legal theory. The common insight animating the word work of these philosophers and “gangsta” poets-Nas and Nietzsche, Davidson and dead prez, Wittgenstein and Ice Cube, Lakoff and The Last Poets-is that “truth” in matters of morality and justice is “a mobile army of metaphors,” a ceaseless struggle over metaphorical re-description, a pitched political battle over the range of application of words and symbols.

II. On “Good Negro Theory” and “Nigga Theory”

Drawing on the N-word's conceptual and political utility, this Part constructs a model, which I will call “Good Negro Theory,” of the values, beliefs, and assumptions that underlie efforts to morally and politically distinguish between law-abiding “good Negroes” and law-breaking “Niggas.” But first, to fiercely contest Good Negro Theory, I will expound “Nigga Theory.”

A. On “Nigga Theory” and the Centrality of Class

I use the term “Nigga Theory” to refer to a group of interlocking proofs and performances aimed at destroying the distinction between disproportionately privileged law-abiding blacks and disproportionately poor black criminals and promoting solidarity between them. To be sure, many of the proofs and performances underling Nigga Theory have the potential to also promote solidarity between all law-abiders and all criminals regardless of race or class. However, because black males bear the brunt of our current blame and punishment practices, because stereotypes and prejudice make black criminals especially likely to stoke the retributive urge in ordinary Americans, and because many misguided black leaders, lawmakers, scholars, and prosecutors have supported and still support the mass incarceration of young black males at the core of the crack plague and its aftermath, it is apposite to term this group of proofs and performances Nigga Theory.

Now, a model. Nigga Theory:

1) Focuses on the moral and criminal condemnation of largely poor black males whose criminal status makes them “niggas” or “bad Negroes” according to critics; and

2) Addresses itself especially-though certainly not exclusively-to black leaders, lawyers, jurors, voters and ordinary folk.

Critical to an understanding of Nigga Theory is an understanding of the role class has played and continues to play in the social construction of “niggas.” As the careful studies of Ruth Peterson and Lauren Krivo on the links between race, place, class and crime in the urban black community demonstrate, the vast majority of “violent crimes” Americans worry most about-murder, manslaughter, robbery, aggravated assault-are committed by “extremely” disadvantaged blacks, not the black bourgeoisie, whose crime rates are much closer to those of their white middle and upper-middle- class counterparts. In terms of violent crime, bad Negroes are disproportionately truly disadvantaged blacks living in extremely disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Good Negroes, by contrast, disproportionately come from the ranks of middle and upper-middle class blacks living in much better neighborhoods. As one of both the wealthiest and wealthiest majority black areas in the United States, and as part of the single largest geographically contiguous middle and upper-middle class black area in the United States, the hills of View Park that I call home might be the Good Negro capitol of America-it is brimming with well-to-do and hence relatively law-abiding Negroes.

For going on two generations now, the working class and poor black neighborhoods that surround my own predominantly black and prosperous “Golden Ghetto” South Central, The Jungle, Inglewood, Watts, and Compton-have hemorrhaged staggering numbers of young black men into prison yards and juvenile detention centers. The flow of poor blacks from bleak streets to cell blocks turned torrential in the mid-1980s with the onset of the crack plague and enactment of laws like the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which ushered in a new era of mandatory minimum sentences for possession of specified amounts of cocaine and a 100-to-1 sentencing disparity between distribution of powder and crack cocaine. Ironically or fittingly, depending on the interpretation of the observer, these laws were co-sponsored by Mickey Leland, chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, and Harlem congressman Charles Rangel and supported by most members of the Congressional Black Caucus. Truly disadvantaged black males took the brunt of these severe new sanctions. Thanks in part to the actions and attitudes of these and other largely middle-class black leaders toward largely poor black male wrongdoers, nearlytwo generations of poor black males have been hobbled if not lost. That so many black leaders and lawmakers, i.e., good negroes, played a leading role in the mass incarceration of black wrongdoers-especially young black males-should come as no surprise in view of the aforementioned “niggerization” of black criminals in both popular culture and legal discourse during the crack plague and in its festering aftermath.

Class plays a central role in the social construction of “niggas”-in whether we explain their wrongdoing in terms of their own internal moral deficiencies or instead in terms of external social factors and structural determinants-because being broke, like being a criminal, means being viewed as morally deficient by millions of Americans. Put differently, millions blame poverty solely on blameworthy poor people just as they blame wrongdoing solely on blameworthy criminals.

Fifty years ago Michael Harrington's extraordinarily influential book, The Other America, debunked the then-popular belief that America was a classless society by shining a light on the “invisible” poor, especially inner-city blacks, Appalachian whites, farm workers, and the elderly. But his explanation of poverty absolved middle-class America of accountability for the plight of the poor by attributing poverty not to macro-level social factors like social inequality or the simple absence of jobs but instead to the absence of proper values and dispositions in poor people themselves, that is, to their twisted proclivities and “culture of poverty.” In Harrington's words, “[t]here is . . . a language of the poor, a psychology of the poor, a worldview of the poor. To be impoverished is to be an internal alien, to grow up in a culture that is radically different from the one that dominates the society.”

The celebrated Moynihan advanced a similar view, attributing inner-city poverty to deficiencies in the structure of the “Negro family.” Harvard urban government professor Edward C. Banfield-head of the Presidential Task Force on Model Cities under Nixon and advisor to Presidents Ford and Reagan-put it this way, “the lower-class individual lives from moment to moment. . . . Impulse governs his behavior . . . . He is therefore radically improvident: whatever he cannot consume immediately he considers valueless. . . . [He] has a feeble, attenuated sense of self . . . .

In the Reagan years, the “culture of poverty” hypothesis ripened into plump orthodoxy; it became received wisdom that the cause of poverty was not macro-level social factors like meager wages, galloping unemployment, and economic inequality, but rather the internal deficiencies of the poor, who, as Barbara Ehrenreich points out, were viewed as “dissolute, promiscuous, prone to addiction and crime, unable to ‘defer gratification,’ or possibly even set an alarm clock.” Even Bill Clinton formulated and implemented policies guided by “culture of poverty” thinking. Indeed, much legislation enacted by both Democratic and Republican lawmakers today remains imbued with this perspective.

So from the standpoint of Nigga Theory, those who deny our collective accountability for the plight of both criminals and the poor-call them Deniers- are bi-partisan and committed to the same logic of denial. A logic that discounts macro-level social explanations of crime and poverty, and instead adopts (or gives undue weight to) individual-level explanations centered on the “moral poverty” of the poor, the “moral poverty” of criminals, and hence the hyperconcentrated “moral depravity” of poor black criminals, who get whipsawed by both class and race stereotypes and thus are especially likely to stoke the retributive urge. From the perspective of Nigga Theory, poor black criminals belong to a special category of hyperconcentrated otherness that makes them easy to hate-a profound otherness that the words “nigger” and “nigga” capture with fierce felicity.

The retributive urge, even in the black community, to blame and punish “niggas,” fueled by ingrained stereotypes of black wrongdoers as morally deficient and depraved, and further stoked by their niggerization in popular stage acts, books, and op-eds by black entertainers, scholars, and commentators, makes the claims of Deniers more persuasive to many ordinary law-abiding Americans. This urge makes it harder for them to recognize the structural determinants of-and hence our collective accountability for-what I will call “the cataclysmic crack plague and its festering aftermath,” a monumental and roughly 30-year-long crime and incarceration disaster that first struck black America in the mid 1980s, and which has inflicted as much misery on the black community as a thousand Hurricane Katrinas slamming a thousand Ninth Wards. To be more concise, our urge to blame and punish black wrongdoers helps ordinary Americans deny our collective accountability for the foreseeable criminal acts of poor blacks stranded in forsaken neighborhoods brimming with guns and drugs. I will show, in other words, how an inflamed retributive urge toward so-called niggas causes voters, jurors, judges, lawmakers, and others to ignore, deny, or downplay the role of macro-level social factors (for which we are collectively accountable) in both the production and construction of black criminals. I will trace the following links between the process of niggerization, the retributive urge, and America's collective denial of accountability:

· The better wrongdoers fit the “depraved nigga” stereotype, the more they stir the retributive urge for blame and punishment;

· The more wrongdoers stir the retributive urge, the easier it is for Americans to deny a causal connection between the specific criminal acts of poor black wrongdoers and general social facts like racism and joblessness;

· Finally, the easier it is to deny that social forces cause criminal wrongdoing, the easier it is to deny our collective accountability for the crack plague and its legacy.

In short, I will show how the powerful urge to damn and condemn “niggas” induces us to deny our collective accountability for the criminal consequences of being broke, black and hopeless in post-civil rights America.

However, Nigga Theory is not just descriptive. Nigga Theory is also prescriptive, and rests on the hopeful and optimistic premise that once the moral basis for the retributive urge toward black criminals is shown to be illegitimate, irrational and unreliable, it may become easier for fair-minded Americans to curb the urge to condemn such wrongdoers and recognize our collective accountability for their plight and the causal links leading to their plight. For example, consider the last 30 years of crime and incarceration that constitute the crack epidemic and its legacy. There are causal links between those 30 years of crime and the following five macro-level social facts:

· Extreme social and economic inequality in the setting of a cultural belief system sociologists call the American Dream

· The massive flow of jobs from dying rustbelt cities and the stampede of the black bourgeoisie from economically integrated black neighborhoods to economically segregated formerly white ones like my own in View Park

· Well-documented decisions by high ranking U.S. officials during the Reagan and George H. Bush administrations to fight communism by prioritizing foreign policy over drug enforcement and thus knowingly-though not conspiratorially-helping flood poor black neighborhoods with crack in the name of national security,

· Political posturing and opportunism by lawmakers from the Democratic Party, Congressional Black Caucus, and Republican Party on the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 in response to the cocaine-induced death of Boston-bound basketball star Len Bias, resulting in “the criminalization of U.S. foreign policy” through mandatory minimums and gross sentencing disparities for crack-related crimes,

And finally

· Empirically demonstrable unconscious bias in direct moral judgments of black wrongdoers by judges, jurors, lawmakers, police officers, prosecutors, voters and other powerful social decision makers.

These five factors explain both the dramatically disproportionate rates of criminal wrongdoing among poor black males and the lack of empathy for them in jury boxes, legislative chambers, and voting booths.

To help us curb the urge to condemn blameworthy blacks long enough to recognize these five macro-level social factors as the causes of the crack plague and its consequences, I will discredit the twin convictions that undergird the retributive urge toward so-called niggas, namely:

A) our self-congratulatory substantive conviction that persons deserve credit and blame for what they do irrespective of contingency

and

B) our naive epistemological conviction that judges, jurors, and others called upon to make moral judgments of black wrongdoers can do so without conscious or unconscious racial bias.

These twin convictions sanctify the retributive urge by reassuring us that any “niggas” blamed and punished to satisfy it deserve their state-inflicted pain and suffering and solitary confinement and sometimes death. Under Nigga Theory, however, the twin phenomena of moral luck and ubiquitous unconscious bias subvert the support for these convictions both in theory and in practice. My hope is that once the absence of any rational or reliable moral ground for distinguishing wicked from worthy blacks has been exposed, once the urge to blame and punish “niggas” loses its footing in logic and fairness, readers can more clearly see black wrongdoers not as radically “other” moral monsters to be damned, but rather as “social facts” to be deplored and, if necessary, incapacitated and, if possible, rehabilitated, but never, as now, harshly punished in the name of revenge, retaliation, or retribution.

Having described Nigga Theory, I now turn to Good Negro Theory.

B. On “Good Negro Theory” and the “Ostracizer”

For greater precision and clarity, I have coined the term “Good Negro Theory” to refer to the constellation of assumptions, beliefs, and values that undergird the bad Negro-good Negro dichotomy and its corollary contention that law-abiding blacks should socially and politically ostracize black criminals. This interconnected assortment of values, beliefs, and assumptions can be viewed as interlocking tools in an apparatus-call it an “Ostracizer”-designed to advance the social interests of disproportionately privileged law-abiding blacks. The Ostracizer includes:

1. Calibrated Nigga Detector, outfitted with

A) Warning System

and

B) Blaming System,

2. Built-in Excuse Deflector,

3. Double Barreled Distinguish and Distance Device,

4. Good Negro Code of Ethics, and

5. Cost-Benefit, Wealth-Maximizing Moral Compass.

In addition to promoting the social interests of law-abiding blacks, the Ostracizer also helps America, as a collective social actor, deny accountability for the foreseeableconsequences of its criminogenic social conditions and state actions. It does this by reducing crime to the bad choices of morally deficient individuals at whom the retributive urge should be aimed and on whom it should be satisfied.

Below, I describe in more detail each of the Ostracizer's devices.

1. Nigga Detector

The most important device in the Ostracizer is the calibrated Nigga Detector, for bad Negroes must be positively identified before being distinguished, distanced, and disgraced. The calibrated Nigga Detector consists of two separate systems for assessing blacks in criminal matters-a warning system for “suspicious blacks” whom ordinary people would view as posing a heightened risk of wrongdoing, and a blaming system for blacks who actually have done wrong. As part of its warning system, the Detector identifies “patently good” and “suspicious” Negroes. As part of its blaming system, the Nigga Detector identifies “real” Niggas. In keeping with this distinction between warnings and condemnations, the two sources of error that can undermine the Detector's results are: 1) inaccurate predictions about whether a given black person is committing or about to commit a crime and 2) unreliable inferences about the wickedness or mens rea of a black person who has clearly committed a past wrongful act.

i. The Warning System: Assessing Riskiness

First, consider the Detector's warning system, whose sole function is to assess an ambiguous black person's riskiness, specifically the risk that he is committing-or is about to commit-a wrongful act. In this respect the Detector's operation raises issues commonly couched in terms of “racial profiling,” “reasonable suspicion,” “probable cause,” “the Fourth Amendment,” and “criminal procedure.” What is more, the Detector's race-sensitive predictions and warnings reflect ordinary people's risk assessments of ambiguous blacks. In Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism, I dubbed the social price blacks must pay as targets of racial profiling, rooted in racial stereotypes and statistical generalizations, the “Black Tax.”

The Detector's warning system operationalizes the Black Tax by using different sounds, lights, and scrolling electronic ticker tape displays to differentiate blacks according to the kind and degree of criminal risk they appear to pose to ordinary people. Thus, when pointed at “patently Good Negroes” (that is, blacks who ordinary people would view as posing no meaningful risk of wrongdoing, say, nattily clad black Brahmins at a Jack and Jill cotillion in the “Black Beverly Hills” the Detector's warning system warbles melodiously, glows good-Negro green, and scrolls “Safe Negro” across its electronic ticker tape display.

When aimed at blacks who ordinary people would view as dangerous (say, a “big, black man” under ambiguous circumstances), it activates flashing yellow caution lights and differentiates three different kinds of “suspicious Negroes”:

1. Somewhat suspicious Negroes, who elicit a scrolling nigga advisory and a deep monotonous drone like a bee on the wing or humming refrigerator;

2. Very suspicious Negroes, who trigger a scrolling nigga alert and a stream of midrange horn honks; and

3. Imminently dangerous Negroes, who activate a scrolling nigga alarm and high-pitched emergency sirens.

Bear in mind that nigga alarms, alerts, and advisories are predictions and risk assessments rooted in the beliefs, assumptions and perceptions of ordinary men and women. Because the law defines the perceptions and responses of ordinary people as “reasonable,” the Detector's warnings reflect “reasonable” risk assessments of the dangerousness of ambiguous blacks. Of course, appearances can be deceiving, so law-abiding Negroes can trigger false alarms, alerts, and advisories in ordinary people. Nevertheless, in the eyes of the law such false warnings are “reasonable mistakes” as long as they are the kind that ordinary people would make under similar circumstances.

Self-defense claims illustrate how the substantive criminal law treats false nigga alarms. Self-defense doctrine privileges both private citizens and police personnel to use lethal defensive force against persons who reasonably appear to pose an imminent threat of serious harm. The reach of this privilege to shoot scary black males can be exceedingly long, as illustrated by cases like Bernard Goetz, Amadou Diallo, Sean Bell, and Trayvon Martin. Professors E. Ashby Plant and B. Michelle Peruche have conducted experiments with police officers which showed that officers were quicker to decide to shoot an unarmed black target than a similarly situated unarmed white target. Because such discriminatory reactions often occur in the cognitive unconscious, bypassing the actor's voluntary or conscious control, racially liberal and well-meaning officers (and ordinary citizens) arguably cannot help shooting ambiguous blacks more hastily. Because self-defense doctrine excuses ordinary mistakes rooted in ordinary human frailty, the law of self-defense thus allows ordinary police officers and civilians alike to use lethal defensive force more hastily against ambiguous but innocent blacks than against similarly situated whites. So long as ambiguous black men make the trigger finger of ordinary citizens or law enforcement personnel itchier or twitchier in uncertain situations than that finger would be for similarly situated white men, more hasty applications of deadly force to black men will qualify as reasonable and privileged. In the end, then, under current law, the quicker use of lethal force against blacks by ordinary-hence reasonable-and well-meaning police officers and private citizens is an inexorable expression of the Black Tax that black men must simply grin and bear without civil compensation or criminal vindication.

ii. On Race, Place, Class, Crime, and Profiling

Allow me a brief side note. Interestingly, instead of criticizing the use of such profiling, of what I term the general deployment of a Nigga Detector, many in the black community critique only its unfair use on them. It is not the Nigga Detector they object to, but rather the fact that it is still too blunt an instrument, not sufficiently calibrated to exclude all good negroes. These critics add that the disproportionate misdeeds of bad niggas hurt the interests of good law-abiding Negroes by providing the statistical justification for the “Black Tax.” As Ellis Cose chronicles in The Rage of a Privileged Class, the Black Tax is the bane of the existence of the black bourgeoisie and one big reason black Brahmans feel so enraged. Indifferent as lightning, the Black Tax strikes both black haves and black have-nots, both good and bad Negroes. But unlike natural lightning, which in myth never strikes twice in the same place, bolts of Black Tax lightning repeatedly strike the same targets again and again. This phenomenon is shown by a Community Service Society of New York's analysis of 2009 stop-and-frisk data for the New York police: there were 132,000 stops of black men 16-24 in 2009 (94 percent of which did not lead to an arrest). According to Census Bureau data, only 120,000 black men of that age lived in New York City in 2009! Thus, “on average, every young black man can be expected to be stopped and frisked by the police each year.” Put differently, young black men in New York are law- enforcement lightning rods who can expect to be struck over and over by blue surge bolts of Black Tax lightning.

Some privileged blacks would not find the Black Tax so infuriating if it were more targeted, tailored, and regressive, that is, more limited to poor blacks, whose disproportionate misdeeds establish and maintain the statistical link between race and crime in the first place. Black Brahmin icon, Bill Cosby, stressed the class factor in his address at the NAACP on the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education: “Ladies and Gentlemen, the lower economic and lower middle economic people are not holding their end in this deal.” Statistically at least, these better off critics of poor blacks have a point: the vast majority of black street criminals are from “extremely” disadvantaged neighborhoods. From this statistical perspective, by committing street crimes at such disproportionately high rates, “poor black criminals” make blackness itself, in the language of evidence law, relevant evidence of criminal wrongdoing or criminal intent. The disproportionate misdeeds of poor blacks-to paraphrase the evidence code-make the proposition that someone did or will do a crime statistically more likely to be true given his blackness than it would be without that factor. This cold but cogent math-chiefly bottomed on the criminal wrongdoing of blacks from truly disadvantaged neighborhoods-has prompted my Black Beverly Hills neighbors to openly declare “We don't want Compton up here”; in eerily similar language it also prompted an L.A. County Sheriff's Deputy to warn an event planner that “We don't want South Central up here.” The cogent math linking extremely disadvantaged black neighborhoods and violent crime means that, from the perspective of these good negroes, someone from such a neighborhood should pose a much greater risk of serious street crime than his Golden Ghetto doppelganger. These good negroes thus embrace something akin to a mapping of the link between race, place, class, and crime, something akin to a “nigga geography” or “nigga cartography.” Not surprisingly, there's an app for that-a service originally launched under the name “Ghetto Tracker” and relying on crowd sourced information (locals rate which parts of town are safe and which ones are ghetto, or unsafe) to help people avoid unsafe areas.

For these good negroes, the Nigga Detector would be less blunt and more finely calibrated if it also included a Ghetto Tracker. For these good negroes, “class” and “place” profiling-”spatial profiling“-is perfectly rational, reasonable, and right. They can echo defenders of racial profiling and say, with the cool precision of Mr. Spock or Data, “it is regrettable but rational to profile on the basis of geography-nothing personal. As long as there remains a statistically rational relationship between extremely disadvantaged neighborhoods and violence, we cannot escape the logical link between geography and dangerousness. Simply put, we must distinguish and distance ourselves from Jungle-South Central-Compton-Inglewood-Watts blacks because doing so enhances our safety; it's not about race or class but safety-again, nothing personal.” Thus an enraged “privileged class” that rails against too blunt racial profiling itself routinely practices spatial profiling without compunction or even a hint of irony.

iii. The Black Tax as a Tithe That Binds

Allow me another side note. Although I have attacked the Black Tax in books, blogs, and law reviews, a silver lining runs through it. To appreciate the consolation I find in racial profiling, start with the well-supported empirical premise that extreme disadvantage breeds street crime. Then add the observation that so long as truly disadvantaged blacks continue to disproportionately commit street crime, their disproportionate misdeeds will continue to statistically justify the use of a Nigga Detector and the resulting Black Tax, and generate the false nigga warnings that rankle and enrage the privileged class. Now add the recognition that more sophisticated Nigga Detectors will never adequately reduce the false warnings visited upon the enraged class of privileged blacks. The silver-lining implication of these three propositions is that the only way for enraged black Brahmins to pay or sing less of the Black Tax blues is to destroy its statistical foundation by lifting poor blacks out of extremely disadvantaged neighborhoods, fixing their crumbling schools, and addressing other criminogenic social conditions that besiege them. In fact, whenever members of the black bourgeoisie are struck by bolts of Black Tax lightning (whenever, say, they nearly get tennis elbow from trying to flag down cabs that won't stop), their rage should give way to a “moment of Zen”-they should reflect on reasons for the sometimes cogent statistical disparities in rates of crime by race that can be advanced to justify racial profiling and its attendant indignities, namely, the hopelessness, frustration, alienation, and despair of truly disadvantaged blacks stranded in neighborhoods abandoned long ago by the “privileged class” itself. The relatively law-abiding black bourgeoisie should view the Black Tax as a “tithe” that binds their fate to that of extremely disadvantaged blacks, a relentless reminder that as long as “they” don't look good, “we” don't look good. That is the silver lining, at least in theory.

iv. The Blaming System: Weighing Wickedness

Next, consider the Nigga Detector's blaming system, the primary focus of this essay and of the substantive criminal law. When aimed at a black person who has already committed a prohibited act or actus reus (for instance, a black defendant in a criminal trial who clearly caused a death or some other serious social harm), the Detector no longer needs drones, honks, or sirens to warn of the risk of someone committing a prohibited act. At this point, the risk of wrongdoing has been realized-the jury believes beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed a wrongful act. So in this phase of its operation, the Detector shifts from assessing someone's riskiness, suspiciousness, and dangerousness to assessing his moral fault, blameworthiness, and subjective culpability. Since the sole function of the Detector's blaming system is to assess a black wrongdoer's wickedness, its operation and application raises concerns commonly couched in terms of “mens rea” (i.e. “criminal intents,” “vicious wills” and “depraved hearts”), “individual choice,” “personal responsibility” and “substantive criminal law.” Once again, the Detector's assessments of a wrongdoer's wickedness or mens rea reflect the moral judgments, perceptions and beliefs of ordinary men and women.

So, when aimed at a black who has already committed a wrongful act, the Detector activates a flashing red “Presumptive Nigga” light while broadcasting the click-clack sound of double barrel hammers cocking in rapid succession. This cocking sound acoustically represents the typical or ordinary inference that someone who commits a wrongful act is wicked, so it acoustically represents our readiness to condemn and ostracize the wrongdoer if and when he fails to refute that ordinary inference of subjective culpability. As Professor George Fletcher observes, if someone commits a prohibited act-say, a jewelry store clerk opens a safe and turns over all the jewels to an unauthorized stranger, or a driver runs over someone lying in the street, or a State Department employee turns over vital state secrets to a foreign government-we typically infer from his wrongful act that he is wickedly dishonest, indifferent, or greedy. More succinctly, we typically infer a bad actor from a bad act. In this sense, someone who commits a prohibited act is presumptively blameworthy. And this is particularly true of black wrongdoers, in part because of the implicit biases we all have. Accordingly, when the Detector is aimed at a black wrongdoer, it scrolls “Prima Facie Nigga” across its display along with an acoustic cascade of click-clacks.

Of course, this typical inference of culpability or presumptive wickedness can be defeated. If the clerk, the driver, and the State Department employee commit their prohibited acts at gunpoint, we cannot infer from their wrongful act anything about their dishonesty, indifference, or greed. All three could claim a full excuse of duress. Excuses, in the words of George Fletcher, “preclude an inference from the act to the actor's character.” But can a Prima Facie Nigga destroy the ordinary inference of wickedness that accompanies wrongdoing by raising or interposing a valid excuse?

A wrongdoer may be unable to assert a valid excuse either because the law does not recognize the kind of excuse he wants to assert or because the jury does not think he deserves the benefit of an excuse the law does recognize. In either case, without an effective excuse, he will be found wicked beyond a reasonable doubt. Accordingly, when the Detector points toward a black wrongdoer unable to raise a valid excuse and hence found wicked beyond a reasonable doubt by a jury, the Detector scrolls “real Nigga” across its ticker while acoustically broadcasting the Blam-Blam of the distinguish and distance barrels discharging twin rounds of Bad Negro buckshot.

v. An Illustration-Application-Demonstration: The Reasonable Poor Black Man Test of Mens Rea

To see the Detector tools in action, let's apply the apparatus thus far to the longstanding debate over broad excuses for black criminals from disadvantaged social backgrounds. Of course, any analysis of criminal excuses must begin with a prohibited act or actus reus-like causing death or giving away vital state secrets. Again, blacks who commit such prohibited acts trigger the Detector's cascading click-clacks and scrolling “Prima Facie Nigga” ticker.

At this point a prima facie bad Negro can seek to assert either a broad partial excuse like provocation and “extreme emotional disturbance” or a broad full excuse like duress and self-defense. In claims of provocation and extreme emotional disturbance, a wrongdoer is partially excused if a “reasonable person in the situation” would have been sorely tempted to lose self-control; in duress and self-defense, he is fully excused if a “reasonable person” (i.e. a person of average courage, firmness and backbone) in the wrongdoer's situation” would have been overwhelmed by the threats or apparent threats. So both kinds of excuse turn crucially on the “reasonable person in the situation” test of subjective culpability. Thus, the reasonable person test provides judges and jurors with a flexible legal vehicle by which they can excuse a wrongdoer on the moral ground that his circumstances, in the words of Mark Kelman, drove a wedge between his “contingent” self-the self that came forward under the unjust pressures of the situation in which he found himself-and some underlying “true” self that could have manifested itself and maintained control if not for those unjust pressures.

The “reasonable or ordinary person in the situation” test of wickedness can be either rigid and “invariant”(i.e. a typical person drawn from the general population, average in mental, emotional, psychological and dispositional make up) or flexible and “individualized” (a typical person drawn from a social subgroup, like a typical battered woman or a typical person suffering from a post-traumatic stress disorder or a typical impoverished, poorly educated and chronically unemployed person). Whether the test is invariant or individualized, the underlying question of legal excuses can be distilled to this: “Should the ‘reasonable person in the situation’ test of blameworthiness in cases of duress and extreme emotional disturbance be individualized to make allowances for the wrongdoer's disadvantaged social background?” Alternatively, in instructing on the reasonable person standard: “Should courts instruct jurors on an ‘ordinary impoverished black man trapped behind ghetto walls' test of reasonableness in claims of putative self-defense, duress, provocation, or extreme emotional distress?” Bear in mind that, at bottom, the “reasonable person in the situation” approach to excuses and subjective culpability depends on jury sympathy. In the words of a Model Penal Code Comment on the reasonable person test in provocation cases, “[i]n the end, the question is whether the actor's loss of self-control can be understood in terms that arouse sympathy in the ordinary citizen.” Sympathy, or its absence, drives our moral judgments of wrongdoers at least as much as-if not far more than-reason or logic or categorical imperatives.“Nigga” from this standpoint is a conclusory label that the object of assessment inspires no sympathy in the observer, commentator or decision maker: individuals are not unsympathetic because they are bad Negroes, they are bad Negroes because they are unsympathetic.

2. Excuse Deflector

The above illustration brings me to the remaining components of the Ostracizer apparatus, beginning with the Excuse Deflector. In seeking to assert excuses based on duress, heat of passion, or an individualized reasonable person test, our posited wrongdoer activates the Nigga Detector's built-in Excuse Deflector, which deflects excuses for blacks on moral, legal, psychological, and political grounds.

i. Morally

The Excuse Deflector brushes aside excuses on two often heard grounds. First, in keeping with the widespread view that sympathy for wrongdoers in criminal matters is misplaced, the Deflector channels sympathy away from the human frailty of the wrongdoer and solely toward the terrible suffering of his victims. From this standpoint, sympathy for victims flatly trumps that for victimizers. Second, in keeping with another widespread viewpoint, the Deflector brushes aside most excuses for black criminals on the ground that excuses insult the dignity of their intended beneficiaries-black criminals-by treating them like animals or things or Pavlovian bundles of conditioned reflexes rather than as persons, that is, as moral agents capable of meaningful choice. Both these classic and oft-repeated reasons for rejecting most excuses (even limited and long-standing excuses like heat of passion on sudden provocation) are captured in the following comment by Professor Stephen Morse:

I would abolish [the provocation defense] and convict all intentional killers of murder. Reasonable people do not kill no matter how much they are provoked, and even enraged people generally retain the capacity to control homicidal or any other kind of aggressive antisocial desires. We cheapen both life and our conception of responsibility by maintaining the provocation/passion mitigation. This may seem harsh and contrary to the supposedly humanitarian reforms of the evolving criminal law. But this . . . interpretation of criminal law history is morally mistaken. It is humanitarian only if one focuses sympathetically on perpetrators and not on their victims, and views the former as mostly helpless objects of their overwhelming emotions and irrationality. This sympathy is misplaced, however, and is disrespectful to the perpetrator. As virtually every human being knows because we all have been enraged, it is easy not to kill, even when one is enraged.

ii. Legally

For reasons like those expressed by Professor Morse, the Deflector turns aside all but a few narrowly framed legal excuses, like involuntary act, maybe limited insanity, maybe very limited duress, and no provocation or extreme emotional disturbance. Many courts arbitrarily-from the standpoint of the culpability principle-limit the scope of excuse claims as a matter of law so that wrongdoers never get to present them to a jury. The Deflector reflects and gives effect to these artificial legal limitations on what kinds of extenuating factors a wrongdoer can get before a jury to potentially arouse their sympathy.

iii. Psychologically

The Deflector more readily rejects and deflects excuses for black wrongdoers than for white ones in order to reflect the role of unconscious bias in moral judgments of blacks by ordinary people. Studies on unconscious discrimination-both in the form of attribution bias and in-group empathy bias that ordinary people are more likely to reject excuses for blacks than for similarly situated whites.

iv. Politically

The Deflector rejects excuses because successful ones gum up both barrels of the Ostracizer's double barreled distinguish and distance “them” from “us” response to black criminals. Full excuses like duress clog up the “distinguish” barrel by making it impossible to “differentiate” the character of blacks who commit prohibited acts from those who do not; partial excuses like provocation clog up the “distance” barrel by reducing murder to manslaughter and hence reducing the moral distance between an intentional killer and the law-abiding rest of us. By deflecting most excuses for black wrongdoers, the Deflector keeps both barrels of the double-barreled anti-lumping political reaction to black criminals unclogged and ready.

3. Double Barreled Distinguish and Distance Device

Once the Deflector has rejected the excuse claims of most black wrongdoers, the resulting absence of valid excuses means the jury will confirm the Detector's prima facie readings by finding the wrongdoer a blameworthy bad Negro beyond a reasonable doubt, thereby triggering the implacable BLAM-BLAM of the distinguish and distance barrels while the words “Real Nigga” scroll across their collective electronic ticker display.

4. Good Negro Code of Ethics

Because the Detector-the conceptual and operational embodiment of the Black Criminal Litmus Test of a Nigga-rejects most excuses for black criminals, any racial justice advocate who “makes excuses” for such odious creatures violates the Ostracizer's Good Negro Code of Ethics, under which ethical advocates must remain faithful to the kind of “morality of means” that inspired Justice Marshall to refuse to make excuses for “thuggery when perpetrated by blacks.” In other words, for Good Negro Theory, distinguishing and distancing good and bad Negroes is an ethical obligation, one that imposes ethical limits on how racial justice advocates should treat black criminals and approach criminal matters. Under Good Negro Ethics, racial justice advocates who fail to morally and legally distinguish and distance black criminals from law-abiding blacks breach their most basic duty to help rather than hurt Black People.

For convenience, let me emphasize that I am using the term “Good Negro” to refer to law-abiding blacks who “ethically” wield whatever influence they have in criminal matters to sharply distinguish morally and legally between black law abiders (other good negroes) and black criminals (bad niggas). Thus, there can be Good Negro Presidents, Senators, Attorneys General, Judges, and Jurors. Good Negro Sheriffs, District Attorneys, Parole Board Members and Probation Officers. Good Negro Scholars, Bloggers and Pundits. And finally, there can be Good Negro Associations and Advocates, like the NAACP under Thurgood Marshall, dedicated to ethically advancing the social interests of African Americans in criminal matters through strategies that “sharply distinguish” between Good and Bad Negroes. From the standpoint of Good Negro Ethics, black activists must not defend black criminals, for it hurts Black People when racial justice advocates carry briefs for niggas.

5. Good Negro Cost-Benefit Wealth-Maximizing Moral Compass

Finally, according to the cost-benefit moral compass of the Ostracizer, excuses-such as an “ordinary impoverished black man trapped behind ghetto walls” test of the “reasonable man”-are bad policy for blacks as a group because excuses keep criminal wrongdoers, including drug dealers, users, and gangbangers, out of jail and on the street, where they can claim more mostly black victims. In short, “A thug in prison can't shoot your sister.” Good Negro legal scholar Randall Kennedy puts it this way: “[i]n terms of misery inflicted by direct criminal violence,” blacks “suffer more from the criminal acts of their racial ‘brothers' and ‘sisters' than they do from the racist misconduct of white police officers.” This wry remark may very well be true. It is not hard to imagine that a given Black gangbanger could inflict more pain and suffering on other blacks than a given bigot with a badge and a gun. It may even be true that, to quote another Good Negro commentator, “Racist white cops, however vicious, are ultimately minor irritants when compared to the viciousness of the black gangs and wanton violence.” From this perspective, calling destructive criminals like gangbangers racial “brothers” or “sisters”-words of solidarity and in-group love-rings as false as calling viciously racist white cops “brothers” or “sisters.”

From a cost-benefit standpoint, many criminal matters pit the interests “us” Black People against “them” Niggas. Thus, “colorblind criminal laws”-that is, laws silent on race and not enacted for the purpose of treating one racial group different than another-whose effects disproportionately burden Niggas can be good social policy for law-abiding blacks. For instance, laws that punish crack offenders much more harshly than powder cocaine offenders (who more often are white) may help Black People more than they hurt Niggas, say Good Negro Theorists, “by incarcerating for longer periods those who use and sell a drug that has had an especially devastating effect on African-American communities.” By the same logic, because urban curfews that disproportionately fall upon black youngsters also help some black residents feel more secure, such disparities may help Black People more than they hurt Niggas. Similarly, because crackdowns on gangs that disproportionately affect black gang members also reduce gang-related crime, Black People may be helped more than Niggas hurt by such racial disparities. And because prosecutions of pregnant drug addicts that disproportionately fall on pregnant black women also may deter conduct harmful to black unborn babies, Black People may be helped more than Niggas hurt by such racial disparities.

Under this cost-benefit or welfare principle-and positing that most blacks in the aggregate are law-abiding-there is no reason to give any special weight to the interests and frustrations of black criminals. As David Lyons describes this approach in Ethics and the Rule of Law, when interests conflict “we should serve the greater aggregate interest, taking into account all the benefits and burdens that might result from the decisions that are available to us.” By this logic, because the social, political and safety costs of excusing black criminals fall mainly on the larger Black People subdivision while the benefits of excusing them are reaped mainly by the smaller Nigga contingent, recognizing general excuses for black wrongdoers fails the cost-benefit test of desirability by burdening Black People more than they benefit Niggas. From this perspective, even if judges, jurors, voters, policymakers and the rest of us make racist, biased or otherwise irrational moral judgments of black wrongdoers, laws and other social practices that help the larger Black People subdivision more than they hurt the smaller Nigga subgroup are nevertheless cost-justified and desirable, no matter how unfair from the standpoint of retribution or the culpability principle.

This completes my outline of Good Negro Theory, an interlocking set of values, beliefs and assumptions rooted in moral and legal theories that conveniently advance the interests of disproportionately privileged law-abiding blacks at the expense of those who are disproportionately extremely disadvantaged.

At the conceptual level, the object of Nigga Theory is to attack every one of these values, beliefs and assumptions and thereby expose the blame and punishment problem for what it really is-not a moral or personal responsibility problem but a political and social one, all the way down. To that end, in other work I attack the legitimacy and reliability of moral and legal condemnations of black wrongdoers on philosophical and empirical grounds. I turn now to the broader social and political implications of not critically interrogating our moral condemnation of black wrongdoers and hence of giving in to the “retributive urge.”

III. The Retributive Urge, Causation and America's Denial of Accountability

Deniers reject our collective accountability for the crack plague and its festering aftermath on two standard grounds:

A) impersonal social forces cannot cause people to choose to do wrong

or

B) even if empirical evidence proves that such forces do cause voluntary wrongdoing in the sense of increasing the rate at which people make wicked criminal choices, the very fact that some or many similarly situated non-criminals chose not to commit similar crimes-the very fact of a wicked choice-cuts off our collective accountability on “proximate cause” grounds.

I critique each of these grounds below.

A. Impersonal Social Forces Cannot Cause Persons to Make Wicked Choices

The first defense Deniers raise against our collective accountability for the crack plague and its legacy is the common assertion that voluntary criminal acts cannot be caused by impersonal macro-level social factors like poverty and social inequality. Stated more generally, the assertion is that voluntary human action cannot be “determined” by social factors or external influences and thus that there can be no “social determinism.” In keeping with this approach, Deniers attribute wrongful behavior to persons and their individual choices rather than to social situations and factors beyond their control. A bad person, Deniers declare, is different than a bad thing, bad event, or bad social fact. We may deplore tsunamis, avalanches or shark attacks, but we would not morally blame these impersonal destructive forces any more than we would blame a rock for falling on one's head, for we reserve blame and praise for persons with wills and character traits. Deniers contend that macro-level approaches offend the personal dignity of wrongdoers by treating them as things or events or Pavlovian bundles of conditioned reflexes without hearts or minds or wills. For Deniers and other proponents of personal responsibility, this is the Achilles heel of all macro-level explanations of wrongdoing and the flaw in the logic of all broad excuses for criminal misconduct: Such explanations and excuses, they contend, deny the personhood of criminals by treating them as bad “social facts” rather than bad persons. Accordingly, personal responsibility champions tell us we must condemn black criminals to show them respect and damn them in the name of their own personal dignity.

Nevertheless, if sound empirical evidence compels the conclusion that criminal wrongdoing is caused by social forces such as extreme social disadvantage, as it overwhelmingly does, then responsibility for the crack plague and its calamitous aftermath cannot so hastily be shifted to individual wrongdoers themselves. A clear causal link between social facts and voluntary wrongful acts paves the way for holding all beneficiaries of the boon we call the American way of life accountable for its criminogenic social conditions. Social science proves the existence of a clear causal link between social facts and personal, private, individual acts. For instance, in his pioneering work, Suicide: A Study in Sociology, Emile Durkheim showed how the seemingly most personal, private, and even “anti-social” decision of someone to end his own existence rather than continue to suffer a weary life-a decision ostensibly rooted only in individual psychology, private thought processes, and personal demons-actually reflects social currents and at bottom is primarily a social (not psychological or biological) fact. The social character of deliberate acts of violent self-destruction can remain hidden if we look only at a separate individual and his melancholy musings; but the social character of suicide leaps into bold relief when we look at rates of suicide. These suicide rates differ among societies, and among different groups in the same society, and they show regularities over time, with changes in them often occurring at similar times in different societies. “Each society,” Durkheim observes, “is predisposed to contribute a definite quota of voluntary deaths.” These regular, predictable, stable patterns of “personal and private” decisions to shuffle off this mortal coil-in short, these systematic suicidal tendencies-cannot be explained purely in terms of psychological facts, individual mental states or random aggregations of dire deeds. Rather, these patterns point to underlying causes that produce suicidal thoughts and acts in groups of individuals. The decisive question then is, “what factors explain these group-level patterns of voluntary self- destruction?” Earlier, I identified five macro-level social factors that explain the crack epidemic and the empirical evidence that points to them. But even if empirical studies persuasively establish that crime is driven by social factors like the five I identified, Deniers commonly fall back on the following seductive but false “proximate cause” defense against collective accountability for the voluntary misdeeds of wrongdoing.

B. Even if Social Facts Can Cause Crime, the Wicked Choices of Criminals Break the Causal Chain and Absolve Us as a Nation

Deniers' second and most formidable defense against America's accountability for undoing an entire generation of blacks through unnecessary and unwarranted mass incarceration runs thus: “Even if we acknowledge what the empirical evidence clearly demonstrates, namely, that macro-level social factors can cause people to commit voluntary criminal acts in the sense of dramatically increasing the rate of wrongdoing in certain neighborhoods and for certain social subgroups, why don't criminogenic social forces cause everyone subject to them to turn to crime? Why doesn't everyone who is poor, hungry, and socially marginalized rob convenience stores or post up under lampposts with palms full of dope? Why do so many poor and jobless people in general-and poor jobless blacks in particular-wade through criminogenic social currents without turning to violence or larceny or other wrongdoing?” To bolster the persuasive force of these denials of accountability, the person posing these skeptical questions may himself or herself be someone poor and black and extremely disadvantaged-a political poster child for bi-partisan Deniers and other champions of personal responsibility-who nevertheless resisted temptation and provocation to remain law-abiding and hence righteously critical of have-nots who have not. From this perspective, the very fact that many or most people subject to ‘criminogenic’ social factors do not commit such acts proves that such factors leave ample room for peoples' wills and moral character and moral agency to determine what they do. By this logic, the reason poor but law-abiding Americans suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune with self-control while criminals do not is simply because the non-criminals have more moral fiber. For Deniers, the “vicious wills,” depraved hearts, and blameworthy choices of black criminals break the causal chain between criminogenic social facts and individual criminal acts and thus absolve America of accountability for the crack plague and its aftermath.

Deniers can find strong support in law and everyday morality for their contention that voluntary human action breaks the causal chain and thus cuts off the accountability of earlier individuals or entities that “set the stage” for subsequent wrongdoing. A core tenet of American civil and criminal law is that for an individual or entity to be accountable for harm resulting from destructive forces it unleashes (including destructive social forces), those forces must be the “factual cause” and the “proximate cause” of the resulting harm. Factual cause (sometimes called the “but-for” or “sine qua non” requirement) means that the resulting harm (here, the cataclysmic crack plague and its festering aftermath) would not have occurred without the defendant's acts (here, without the five macro-level social facts attributable to America's collective life and social reality). Proximate cause means that the defendant's acts, in addition to being a but-for cause, must be adequately or properly related to the resulting harm in the eyes of ordinary judges and jurors. So, for Deniers and other personal responsibility proponents, even if macro-level social forces are a factual cause of voluntary crack-connected criminal conduct in that such forces can cause dramatic spikes in crime rates as a function of neighborhood demography, these social forces are not a proximate cause of the extra criminal acts. According to these Deniers, this is because the wicked choices of wrongdoers intervened between the extreme disadvantage, on the one hand, and the individual holdups, drive-bys, and street crimes, on the other.

For instance, if a gasoline truck and trailer unit spills a massive amount of gas on an open highway and malicious bystanders willfully kindle a conflagration with a book of matches, some courts refuse to hold the truck owner accountable to innocent burn victims (much less to the malicious match-strikers themselves) because these courts conclude that the volatile spill was not the “proximate cause” of the resulting flames, even though it was clearly a necessary condition or factual cause of the fire. These courts say that the malicious match-strikers are the “superseding,” “efficient,” or “proximate” cause of the fiery destruction, thus shifting the entire responsibility for the flames to the willful wrongdoers and away from the truck owner whose volatile spill set the stage. For these courts, results (here, fiery destruction) that follow from the voluntary actions of the subsequent persons (here, the malicious match strikers) are caused by them alone.

This notion is sometimes called the doctrine of novus actus interveniens. Under the novus actus doctrine, later voluntary human action “displaces the relevance of prior conduct by others and provides a new foundation for causal responsibility.” Glanville Williams provides the classic defense of the doctrine:

A person is primarily responsible for what he himself does. He is not responsible, not blameworthy, for what other people do. The fact that his own conduct, rightful or wrongful, provided the background for a subsequent voluntary and wrong act by another does not make him responsible for it. What he does may be a but for cause of the injurious act, but he did not do it. His conduct is not an imputable cause of it. Only the later actor, the doer of the act that intervenes between the first act and the result, the final wielder of human autonomy in the matter, bears responsibility (along with his accomplices) for the result that ensues.

From this perspective, the violent and non-violent criminal acts of blacks during and after the cataclysmic crack plague are caused solely by them.

By analogy, for the 30 years encompassing the crack plague and it's still festering aftermath, America flooded black neighborhoods with combustible criminogenic conditions like extreme and concentrated social disadvantage; moreover, according to Senate transcripts and other reliable sources, in the critical period between 1982 and 1988, this nation, through its policymakers and high ranking government officials, helped jumpstart and fuel the crack epidemic by knowingly (but not maliciously or hatefully) helping supply many matchbooks in the form of guns and drugs to young black males wading through these volatile conditions. But, whereas combustible gas spills do not penetrate the skin of those it contacts, merely providing opportunities for wrongdoers to manifest pre-existing malice, combustible criminogenic conditions penetrate to the mental states of those immersed in them-these conditions mold mental states and thus manufacture malice itself. Specifically, extreme and hyperconcentrated disadvantage produced the hopelessness, resentment, hostility, and alienation-in a word, the malice-that motivate law-breaking, while an ample supply of guns and drugs, at least partly traceable to U.S. foreign policy priorities in the critical early years of the crack epidemic, provide the means and opportunities for the malice to find expression in law-breaking. In short, at the level of motivations and at that of opportunities for wrongdoing, strong empirical evidence points to our collective responsibility for flooding black neighborhoods with combustible criminogenic conditions that tempt, pressure, and provoke, then helping supply rafts of matchbooks to the young black residents in the name of national security.

This is precisely where Deniers invoke the novus actus doctrine as a “proximate cause defense” and assert that the wicked decisions of the individuals slogging through combustible social currents to pick up matchbooks and spread fiery destruction cuts off our collective accountability for their foreseeable and even statistically inevitable but nonetheless voluntary match-striking. For Deniers, in other words, the willful and wicked intervention of match-striking wrongdoers-the voluntary rubbing of each white phosphorous match head against a rough surface to produce a flame-breaks the causal chain between social facts and criminal acts. The results that follow from their voluntary actions are caused solely by them. For Deniers, however abundant the opportunities of the situation or strong the socially molded motivations of the person, choosing to strike a match constitutes a personal and individual “moral moment” that severs the link between social forces and crimes and erects a boundary between social facts and personal responsibility.

Thus, as applied to the crack plague that bore down upon and destroyed black communities in the 80s and 90s like a raging wildfire, Deniers can concede at the level of factual causation that social forces (such as the five macro-level social factors discussed earlier) dramatically increased the rate of crime and incarceration in black America and hence orchestrated the general movement of the fire, the general symphony of the conflagration, but they may nevertheless contend that each individual decision to dance to that malicious melody by striking a match breaks the causal chain between America's volatile social currents and the crackling flames. Put differently, mediating the relationship between social facts and criminal acts are criminal intents and vicious wills and depraved hearts, and for Deniers, these wicked inner states cut off our collective accountability for the criminal acts produced by our collective existence.

C. Competing Doctrine: Later Voluntary Wrongdoing Does Not Break Causal Chain