Become a Patreon!

Abstract

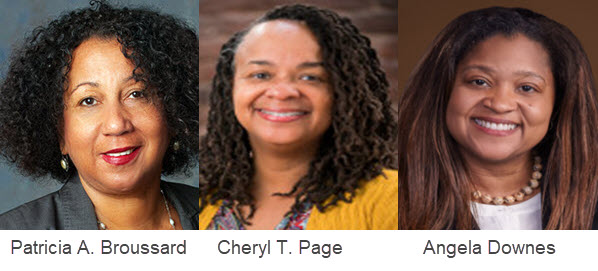

Excerpted From: Patricia A. Broussard, Cheryl T. Page, and Angela Downes, Damn It! A Conversation on Being Black, Female, and Marginalized During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Is the World Listening? , 12 Alabama Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Law Review 1 (2020) (469 Footnotes) (Full Document)

We are African American women with a combined forty-four years in academia. We are professors of law and have seen firsthand how COVID-19 has ravaged African Americans across this country. As we conversed with one another in the Spring of 2020 about what we were witnessing, we began to look through the spectrum of the law and discrimination, and how this novel Coronavirus is laying bare the inequities and inequalities that have been evident for hundreds of years in the Black community. We felt compelled to put pen to paper and document our conversations in an attempt to give a voice to those most negatively impacted by this deadly virus--those that have long been most underrepresented. We hope that by calling out these disparities, we somehow elevate our nation and change the course of the lives of Black women for the better.

The purpose of the paper is to examine how the law, medical institutions, and society (globally and domestically) are grappling with this pressing issue. Our article looks at how certain segments of our population receive vastly different types of care for medical conditions than do similarly situated people of different races, how our society is dealing with these negatives, and how these disparities have rippling effects in society and on the people mistreated. This article looks at how Black women are much less likely to be insured as a group than are White women and how that disparity has caused Black women to be more susceptible to COVID-19. This critique of this pandemic's impact on Black women examines these issues and more, from the firsthand perspective of Black women.

Part One: Gender Matters: A Look at How Covid-19 Has Impacted the Economic and Educational Status of Marginalized Women and Girls Worldwide

Patricia A. Broussard

Query: What secondary economic impact has COVID-19 had on the most vulnerable populations in the world?

Short answer: An economic pandemic has been visited upon women and girls, who are globally the most vulnerable population. has been their plight for decades, if not centuries, and COVID-19 has threatened to divert attention and resources so desperately needed to address their vulnerability. impact of COVID-19 is especially glaring in the areas of extreme poverty and education. In this part of our conversation, I will focus on what COVID-19 has done to negatively exacerbate the impact on women and girls in these critical areas.

[. . .]

This paper contains facts and figures that define the daily lives of marginalized women worldwide. It was written from the comfort of my home. I had food and fresh water available to me on a daily basis despite being quarantined. I had doctors' appointments I was able to attend and pay for. I had air conditioning during the oppressive heat, and I had technology at my disposal. I understand that I am privileged, and as such, I have a responsibility to be a voice for the voiceless and to tell the stories they cannot tell. The intent of this article is not to reduce marginalized women to statistics; rather, it is to emphasize their divine humanity.

Marginalized women and girls appear to be collateral damage to the COVID-19 pandemic. This virus has hamstrung the steady but limited strides previously made in the areas of easing poverty, increasing educational opportunities, and preventing domestic violence. COVID-19 has taken up all of the oxygen in the room. World economies are suffering, which has caused governments to reevaluate their budgetary priorities and reassign and realign resources away from marginalized women's critical needs to aid in combating COVID-19. It is reasonable for governments to allocate resources to provide for the health and safety of their citizens. However, they must also remember that included in their citizenry is a vulnerable population needing greater protection and attention to prevent it from spiraling into a pandemic of hopelessness and death that could rival COVID-19.

Other things must be done to protect women and girls during this pandemic. The first step is an acknowledgement that this pandemic has disproportionately impacted marginalized women, coupled with the commitment that they must be protected at all costs. Secondly, and probably most importantly, women must have a seat at the table where decisions are being made about them. Too often these decisions are made by male contingencies, lacking the necessary and critical input of those most impacted by the situation.

Because poverty is such an issue for marginalized women, they must be given as equal an opportunity to work as men, even in a depleted job market. Governments, which have the ability, can and should institute some sort of minimum income for all in need. In addition, food and medical care should be readily available to the most susceptible. Arguably, this requires cooperation on a global level because, in the event of a food shortage, as predicted, countries will seek to protect their own citizenry first. In the United States, social safety nets must be expanded to create a safe space for women living on the edges of poverty.

Also, schools and schooling must be made a priority for girls. Previous efforts to curtail the barriers preventing girls from receiving the education they so desperately require must continue. Governments must mitigate the effects of the virus on girls through effective planning and by financing initiatives to get them back into schools and keep them there. It is imperative that there be adequate funding both during the pandemic and for the years to come after. Governments must do more to address the issue of violence against women and girls if they are serious about educating them. Supporting these victims should be a priority.

Lastly, governments must uplift marginalized women and girls during and after COVID-19. In doing so, they are lifting up the health and well-being of their countries. They must actualize the notion that "women hold up half the sky," by ensuring that they survive, prosper, and receive the education they so richly deserve. In doing so, they must acknowledge the fact that women are human.

Part Two: A Tale of Two Patients: How Covid-19 Has Unmasked the Inequalities Experienced by African American Women

Professor Cheryl T. Page

Query: How has COVID-19 hurt African American women with respect to discrimination in health care in America?

Short Answer: COVID-19 has exacerbated health care disparities for African American women by exposing the conditions and gaps that existed previously. Some of these are a general distrust of medical professionals given past exploitation and racist practices. Many African American females have lower and lesser access to quality health care, which worsens many health outcomes. Many of these women live in food deserts, which cause a poor diet and increased stress levels. And they live in multi-generational homes that are more likely to be crowded and where social distancing is not feasible. Perhaps the largest factor that leads to the disproportionate deaths of African Americans is the fact that many are "essential workers," on the front line of this pandemic, with little to no personal protective equipment. This essay will focus on these and other factors that cause African American women to be in a position to die in greater numbers than they represent in this country.

[. . .]

As we have seen all too clearly, COVID-19 has shown itself to not be an equalizer but a magnifier. It has worked to expose all of the inequities that have been plaguing African Americans for decades and laid bare all that is unjust in America. Thankfully, the CDC has made it clear that "[r]educing racialdisparities in healthcare requires national leadership to engage a diverse array of stakeholders; facilitate coordination and alignment among federal departments, agencies, offices, and nonfederal partners; champion the implementation of effective policies and programs; and ensure accountability." The studies and findings above can help motivate increased efforts to intervene at the state, tribal, and local levels to best address health disparities and inequalities.

As we strive to better understand current racialdisparities in health care, we become more aware of the racism that has operated and continues to operate today. By attempting to attack prejudice, stereotypes, and negative stigmas of minority groups, we can help to establish trust within the medical community and the profession as a whole.

As a civilized society, we must recognize the need and benefit of living in a society where all citizens have access to fair, equal and equitable, quality health care. We must work to ensure that the most vulnerable and marginalized in our society are taken care of medically. So that when those two racially different people enter the emergency room with COVID-19, we as a country should be able to recognize that both deserve the same level of treatment, regardless of racial status, ethnicity, or education level. How we treat certain segments of our national community is indicative of our moral character as a country.

Part Three: The Impact of COVID-19 on Black Women Essential Workers

Angela Downes

Query: What do we tell our young daughters about their place in the world as employees and workers during this time of COVID-19 as we watch them grow to be Black women? Why hasn't there been a greater evolution of Black women and their role as essential workers in American society? COVID-19 has shined a spotlight on the historical struggles of Black women as essential workers. Time continues to move, but the narrative has not.

Mine is a privileged existence. My family and I have the luxury to shelter in place. Once the country shut down and businesses began to shutter, I seamlessly began to teach law school classes online, my husband was able to stay home while a strategy was developed and implemented at the company where he works, and my child attended online classes. We had groceries and other essentials delivered and went for daily walks in our neighborhood--closely monitoring the news distressed by the rising number of deaths. My hardship centered on managing the number of Zoom calls that my husband, daughter, and I had each day. I know that mine is not the typical situation for so many Black women in America.

[. . .]

The current situation surrounding COVID-19 continues to steadily deteriorate. With the lack of a comprehensive coordinated federal response, individual states and cities scramble to ensure that the health and safety of their communities while navigating an uncertain economy. In order to safeguard our communities, and especially Black women essential workers, we must work on promoting the following policies.

Conclusion

The long-term effects of COVID-19 will not be known for years. It is a catastrophe of our own making. For Black women essential workers concerned with survival while still supporting their families, we must implement measures on all levels that ensure a rapid recovery while addressing systems of privilege and longstanding disparities. We are a nation of compassion, empathy, and grace, traits that should be incorporated in our response to the pandemic. Years from now, when archeologist explore and study the Black women of today, what will represent the cowrie shells? Angela had four cowrie shells - what will be the symbols that the archeologists of the future will find for the current essential Black women workers?

In spite of concerted efforts at achieving racial equality and eliminating the chasms that exist for African American women, the subordinate position of African American females persist. As we, African American female law professors, witnessed COVID-19's unprecedented rampage on the African American community, we felt compelled to speak up about these tragic circumstances. It is our desire to be the voice for the millions of women of color, domestically and globally, who have no voice in this conversation.

We hope that we have addressed issues and concerns that are pertinent to all women but especially women most negatively impacted by COVID-19. African American women are strong, resilient, and determined women who have struggled for centuries to lead healthy, whole, and financially secure lives. This is due, in large part, to the persistent effects of outright racism, which impacts all African Americans no matter what their socioeconomic status. While much of what has been discussed paints a grim picture, if our nation (and global community) makes real commitments to eradicating systemic racism, discrimination and inequities, significant gains can be made for those most negatively impacted. Equal pay for equal work, equitable economic opportunities, true educational advances, and equal access to quality health care must all be part and parcel of that effort.

We hope to chip away at multiple disparities facing Black women and bend the arc of justice towards those most marginalized, mistreated, and maligned. Fair and equitable policies are informed by all of America's citizens and all citizens in our global community. We eagerly await the day when our nation takes to heart the intrinsic value of all people by ensuring that we all can live a life that is free from the burdens and weight of discrimination and pervasive injustices.

Patricia A. Broussard is a Professor at Florida A&M University College of Law in Orlando, Florida. She teaches Constitutional Law, Women and the Law, First Amendment, and Advanced Appellate Advocacy. Her scholarship is in the area of women's rights.

Cheryl Taylor Page is a Visiting Professor at Florida A&M University College of Law. She teaches Criminal Law, Evidence, Criminal Procedure, Domestic Violence Law, Civil Rights, and Human Trafficking. Her scholarship is in the areas of human trafficking and human rights.

Angela Downes is a professor at UNT Dallas College of Law in Dallas, Texas where she is Assistant Director of Experiential Education. Professor Downes teaches clinical courses, the 40-hour mediation course, and domestic violence and the law. Her scholarship focuses on diversity and cultural responsiveness and issues of interpersonal violence including domestic violence, human trafficking, and child abuse.

Become a Patreon!